Since the outbreak of war in Sudan, violations have not been limited to being a byproduct of fighting between armed factions. Instead, mounting field testimonies and human rights reports suggest a far more dangerous trajectory: specific ethnic groups most notably the Kanabi communities have been subjected to recurring patterns of violence that go beyond the logic of conventional military operations.

This investigation examines indicators of identity-based, systematic violence and analyzes whether the documented practices amount to a pattern of ethnic cleansing within the context of the Sudanese conflict. It does so by tracing incidents on the ground, patterns of targeting, and the conduct of state forces toward these communities.

European Centre for Strategic Studies and Policy (ECSAP)

Khartoum, London, Stockholm

Along the irrigation canals of Gezira State—where water was meant to nourish crops—bodies began to surface one after another. Men in civilian clothing, some with their hands bound, others shot in the head. These scenes were not isolated incidents amid the chaos of war, but early signs of a systematic pattern of violence accompanying the advance of the Sudanese Armed Forces and their allies across central Sudan.

As the Sudanese Armed Forces regained control of Wad Madani and surrounding areas, accumulating evidence emerged pointing to the targeting of civilians on an ethnic basis. This included mass killings, summary executions, and the systematic disposal of bodies in water canals and mass graves.

Intersecting military and field testimonies indicate that these violations were not the result of individual misconduct, but occurred within the framework of coordinated military operations.

“Anyone who appeared to be from western or southern Sudan was shot immediately,” said a Sudanese army officer with direct knowledge of the field operations, speaking on condition of anonymity.

These events unfold within a war that, according to UN estimates, has claimed more than 150,000 civilian lives and forced nearly 12 million people into displacement—one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises today. Yet what occurred in Gezira State bears distinct characteristics: selective violence targeting specific ethnic groups, justified under the pretext of combating the Rapid Support Forces.

This investigation is based on the analysis of hundreds of field-documented videos, satellite imagery showing sites where bodies were disposed of, testimonies from military officers and security personnel who took part in the operations, as well as interviews with survivors and eyewitnesses from various parts of Gezira State. It also draws on a review of human rights reports and UN investigations that have examined patterns of violations in central Sudan.

In Beika, along the road leading to Wad Madani, and in the vicinity of the Police Bridge, the same account is repeated: unarmed civilians are detained, executed, and then systematically erased.

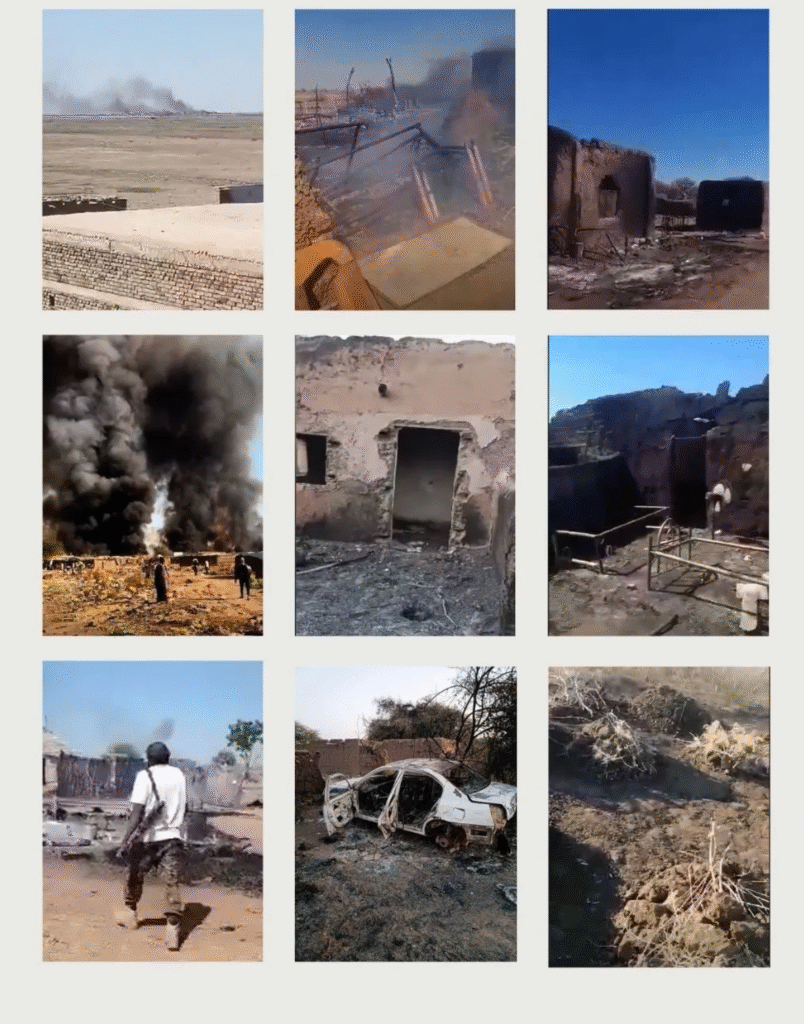

In villages known as kanabi—home to long-marginalized non-Arab communities—the military operations escalated into wide-scale attacks involving killings, arson, and forced displacement.

“It wasn’t just about fighting; it was about cleansing the area,” said a former intelligence commander who oversaw forces in Gezira, a statement that reflects the nature of what unfolded on the ground.

This investigation seeks to answer a central question: How did Sudanese army operations in Gezira State transform into a systematic campaign of ethnic cleansing? Who issued the orders, and what level of evidence exists to situate these crimes within the legal framework of war crimes and crimes against humanity?

What emerges from the documents, testimonies, and visual evidence suggests that what occurred was not merely another bloody chapter in an open war, but a war crime carried out in silence—targeting people on the basis of identity.

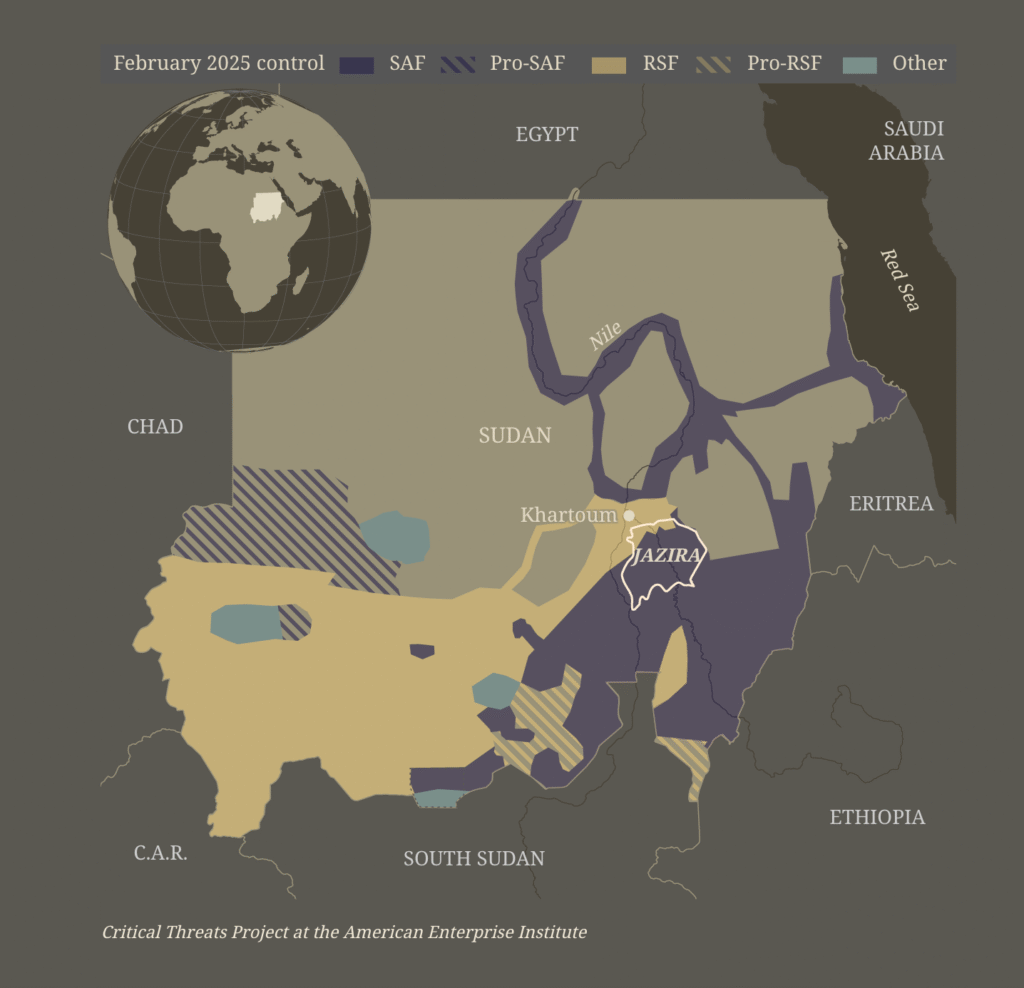

From the Recapture of Wad Madani to Killings Based on Identity. When the Rapid Support Forces withdrew from large parts of central Sudan—ostensibly to spare civilian lives after nearly a year of control—the Sudanese Armed Forces and allied militias entered Gezira and Sennar states in two successive waves between October 2024 and January 2025.

On the surface, these operations appeared to be a “restoration of control” over strategic cities and roadways. On the ground, however, according to field testimonies and verified visual material, the military return was accompanied by organized campaigns of violence targeting unarmed civilians. These attacks bore a clear ethnic character, particularly against residents whose origins trace back to western and southern Sudan and the Nuba Mountains.

“There will be no more kanabi… you are gharaba (outsiders)… and outsiders must be uprooted from Gezira,” one survivor from the kanabi communities recounted, describing what attackers told them amid shootings, looting, and arson.

Gezira lies directly south of the capital, Khartoum, encompassing the state’s main agricultural lands—areas that have repeatedly changed hands between the warring parties throughout the conflict.

According to corroborated field data, the violations were not confined to the city of Wad Madani alone, but extended along major transportation corridors: Sennar–Madani, Madani–Khartoum, Al-Fao–Madani, and Managil–Abu Qouta–Khartoum, as well as villages east and west of Sennar, reaching as far south as Al-Dinder (including villages such as Al-Kamarab, Abd al-Banat, Manofali, and Al-Farish).

Across these areas, the same pattern repeatedly emerged: mass arrests, extrajudicial killings, torture, unlawful detention, forced displacement, and the systematic looting and burning of homes and property.

“The Canal” as a Crime Scene

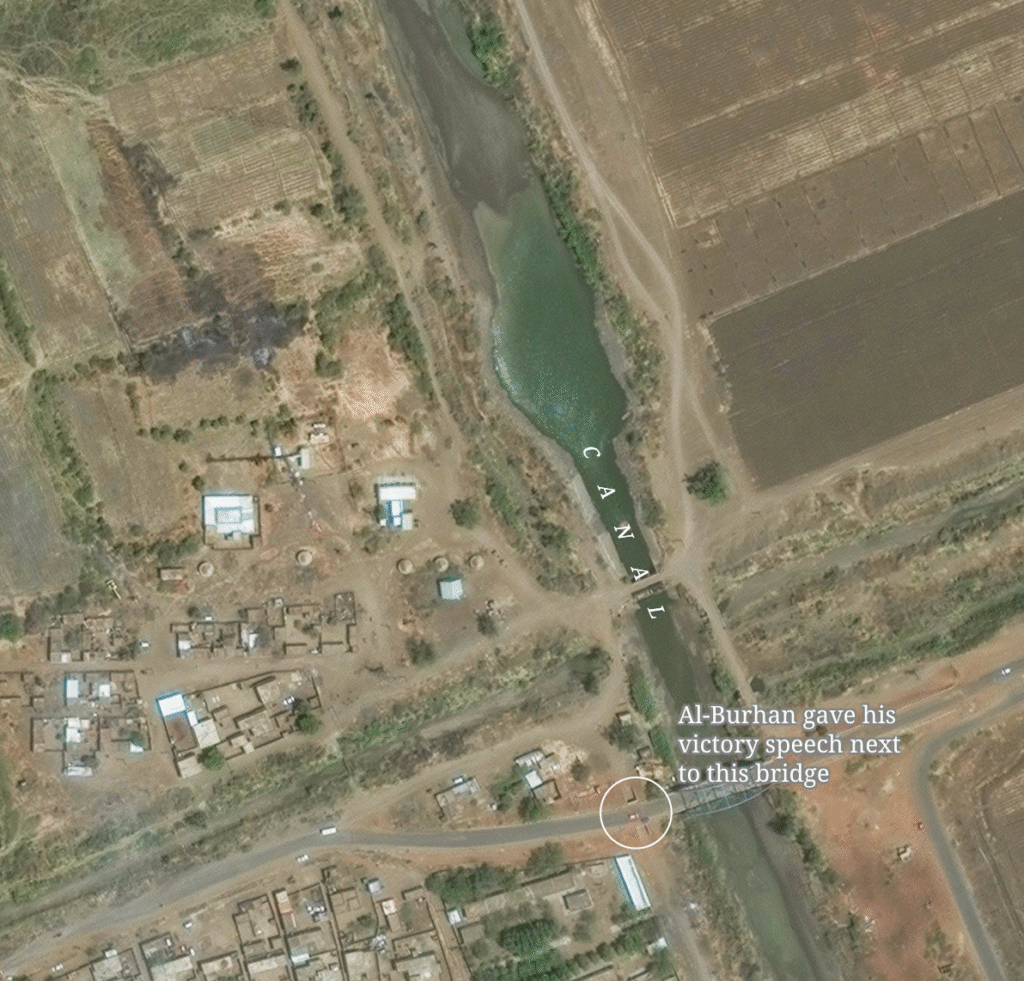

Just days after Sudanese army forces entered Wad Madani (12 January 2025), bodies began appearing in large numbers at specific points along the main irrigation canal linked to the Gezira Scheme, particularly near the Al-Ma‘ailiq sluice gate/bridge (Al-Ma‘ailiq–Al-Dubaiba Abdallah).

Military testimonies indicate that the killings did not begin at the bridges themselves, but occurred extensively west of the city, where a campaign was launched against nearby kanabi communities. Residents were arrested and killed “immediately,” after which their bodies were thrown into the canal or buried in nearby locations.

“There were many of them… I personally saw around 500 people,” says a military source who was part of the participating forces, referring to mass arrests in adjacent kanabiand killings followed by dumping bodies into the canal.

In the Biqa area and its surroundings, testimonies recount an additional narrative: hundreds of civilians who had come out chanting in what they believed was a “welcome” for the forces were shot at, after which a large number were buried in a mass grave near the entrance of the Police Bridge on the western bank, according to field sources.

In the days and weeks following the advance of the Sudanese Armed Forces toward Wad Madani, bodies began floating to the surface of the same canal system. Videos published online on 18 January—whose geolocation we verified at a bridge less than 80 kilometers north of Al-Buqa‘—show at least eight bodies trapped in the water.

All of the bodies were either naked or dressed in civilian clothing, and at least one had his hands bound behind his back. Water flows northward through the Gezira canal system between Al-Buqa‘ and the location where the bodies were found, a pattern that aligns with whistleblower accounts as well as expert testimony and analysis indicating that the bodies were carried by the current from areas near Wad Madani.

Lawrence Owens, a forensic anthropologist who reviewed the footage, said the victims appeared to have died approximately a week earlier—a timeframe consistent with the Sudanese army’s campaign to seize control of the city.

These incidents cannot be viewed in isolation. They intersect with additional visual material and photographs captured at multiple points along the canal, showing bodies arriving daily over several consecutive days. Some were reportedly retrieved and buried near the canal and the railway line in areas such as Abu Ashar (near the Chinese Hospital), according to local testimonies.

The Kanabi: From Workers’ Settlements to Military Targets

The kanabi are not ordinary villages in their social makeup. They are informal, unplanned labor settlements that historically emerged on the margins of the Gezira agricultural scheme, inhabited largely by agricultural workers, many of whom trace their origins to western Sudan. During the military operations, these communities were treated as alleged “support bases” for the Rapid Support Forces a broadly applied accusation that, according to testimonies, was used to justify killings and forced displacement.

In Al-Hasahisa, for example, survivors described attacks on more than 16 kanabi, involving indiscriminate gunfire by the Sudanese army, arrests on accusations of collaboration, looting, arson, and the destruction of property including cars, motorbikes, and even mature trees. In one incident, a witness said attackers encircled a kanab from all sides while chanting slogans calling for eradication and cleansing.

“They burned six cars and nine motorbikes… and cut down trees that were 35 years old and took them with them,” said one survivor from the Al-Hasahisa area in testimony to the investigation team.

A report by an independent UN fact-finding mission, published on September 5, 2025, noted that after control of Gezira State was retaken in January 2025, retaliatory attacks particularly targeted kanabi communities. The report documented dozens of killings over a short period (January 9–12, 2025) in attacks attributed to army forces, describing a consistent pattern: armed vehicles, gunfire against unarmed civilians, the burning of homes, looting of livestock and property, the use of racist slurs such as “slaves” and “ghuraba,” and the prevention of residents from returning.

In a speech on January 16, Sudanese army commander and head of the Transitional Sovereignty Council Abdel Fattah al-Burhan boasted that his forces had carried out an attack on Rapid Support Forces fighters in the same area—an operation documented in a video published on social media that same day.

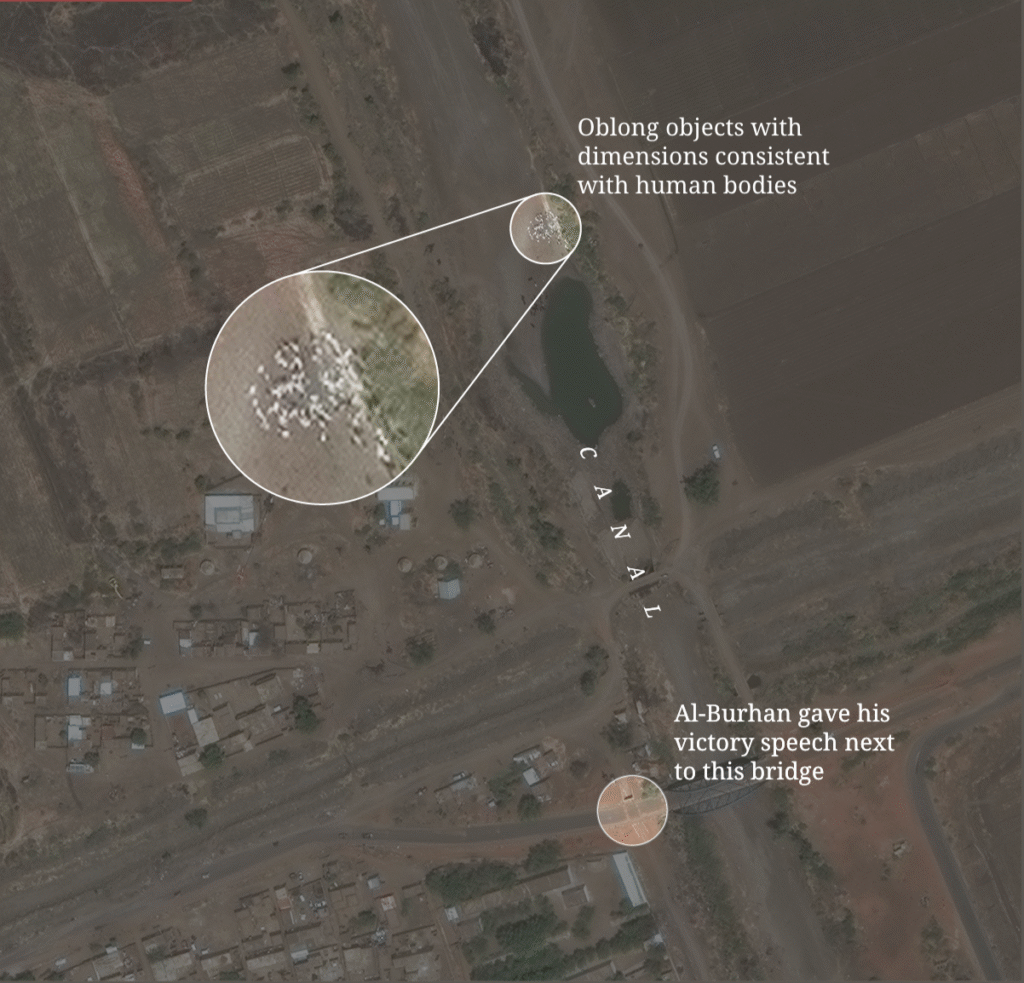

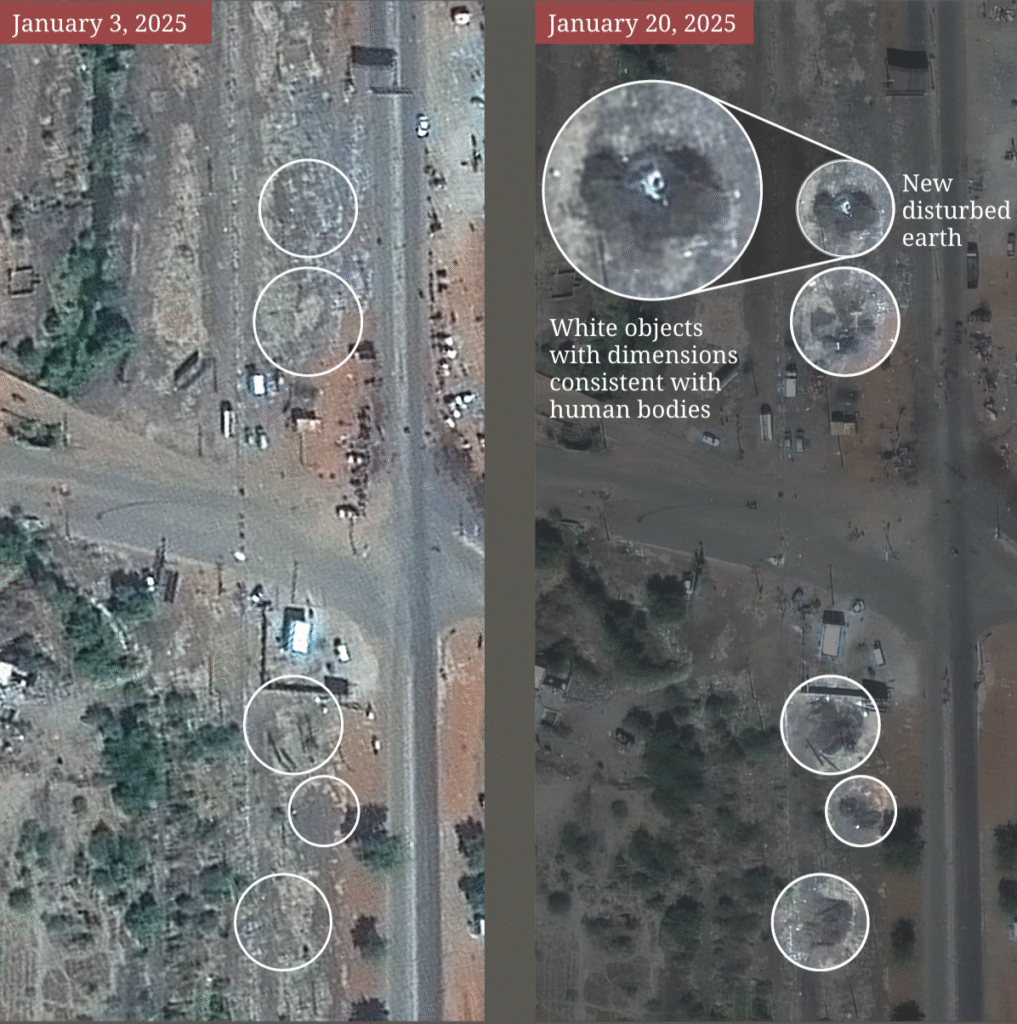

As the waters in the Gezira irrigation canals receded in the spring, more evidence emerged. Satellite images captured in May revealed what appear to be dozens of additional bodies disposed of in the canal in the Bikka area, just a few meters from the site where al-Burhan delivered his victory speech.

Images analyzed by the Humanitarian Research Lab at Yale School of Public Health showed the presence of multiple white shapes on the canal bed, whose size and appearance are consistent with wrapped human bodies.

This investigation relied on a multi-layered verification methodology, including the analysis of hundreds of field-documented video recordings, with their locations geolocated by matching visible landmarks against recent satellite imagery. The timing of the footage was also cross-referenced with troop movements on the ground and fluctuations in water levels within the irrigation canals.

In addition, direct interviews were conducted with eyewitnesses and survivors, as well as military sources familiar with the operations. Their testimonies were cross-checked against independent human rights reports and United Nations documents to ensure accuracy and to exclude unverified or misleading accounts.

How were the locations and incidents verified?

The images of bodies floating in the main irrigation canal in Gezira State were not treated as fleeting, shocking clips circulating on social media. In this investigation, the material was handled as evidence from an open crime scene and subjected to a multi-layered verification process that included geolocating the footage, establishing timelines, reconstructing the sequence of events, and cross-checking visual evidence with firsthand testimonies and on-the-ground indicators.

The investigation team conducted precise visual matching between videos showing bodies floating or clustered in the canal and fixed landmarks on the ground. These included known water control structures such as the Al-Mu‘ayliq sluice (Al-Dubayba Abdallah), local bridges like Beika Bridge and Police Bridge, irrigation control gates running alongside the Blue Nile, and railway lines adjacent to the canal in areas such as Abu Ashar.

This geolocation process showed that most of the footage was filmed along the main canal—locally known as the “Kannar” or “Major”—north and west of Wad Madani. These areas were not scenes of direct combat at the time the incidents occurred. This finding rules out the possibility that the deaths resulted from battlefield clashes and instead supports the hypothesis that the victims were killed after full military control had been established.

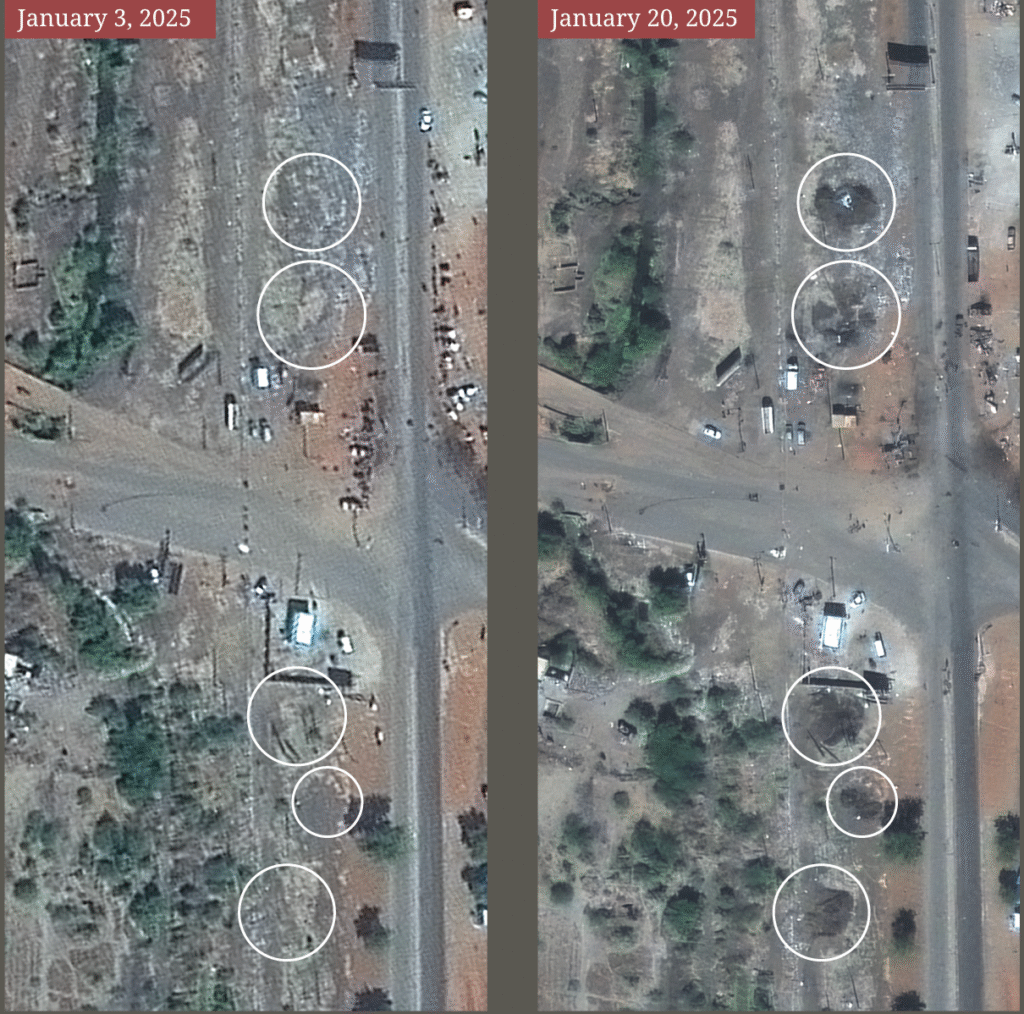

In parallel, the timing of the footage was analyzed by examining water levels in the canal and the visible stages of decomposition of the bodies, and then correlating these observations with the entry of the Sudanese Armed Forces and allied units into Wad Madani on January 12, 2025.

These findings align with eyewitness accounts from multiple locations. In the three to five days following the military’s entry, bodies began appearing near the sluices. For approximately a week thereafter, residents in areas such as Abu Ashar and Wad Al-Sayyid reported bodies arriving daily via the canal. Later, some bodies were retrieved and buried at sites close to the canal, sometimes using heavy excavation machinery.

A witness from Abu Ashar said: “The bodies were arriving every day… we pulled some of them out and buried them near the canal.”

Military testimonies further corroborate the visual evidence. More than one military source who participated in or had knowledge of the operations stated that the killings were not random acts of violence, but part of organized “sweep” operations targeting the kanabi settlements west of Wad Madani particularly in Wad Al-Na‘im, the Beika area, and the kanabi along the Wad Madani–Managil road.

Experts noted that the attacks primarily targeted people of non-Arab origin, including residents from Darfur in western Sudan and individuals from what is now South Sudan.

Peter Baly, an expert on United Nations human rights mechanisms, said that the documented pattern in Gezira State “shows clear indicators of crimes against humanity, particularly in terms of the systematic targeting of civilian groups based on identity and the organized disposal of bodies to conceal evidence.”

From Killing to Disappearance

What the evidence reveals goes beyond acts of killing alone; it outlines a complete and coherent pattern of criminal conduct. The process begins with mass arrests based on suspicion or identity, followed by extrajudicial killings—either in the field or while in detention—and then the systematic disposal of bodies. Victims’ remains are thrown into irrigation canals or buried hastily in unmarked graves near waterways or roads, while residents are prevented from approaching the sites or returning to their areas.

At dawn on January 12, the Sudanese army launched a violent assault at Police Bridge. Videos filmed at the scene show bodies scattered across a road intersection, all wearing civilian clothes, surrounded by burned and overturned vehicles.

Other videos from Police Bridge document clear executions of unarmed men in civilian clothing.

Satellite imagery from the same period, reviewed by the Yale Humanitarian Research Lab, shows five newly disturbed patches of earth near Police Bridge. In one of these areas, white shapes consistent with human bodies can be seen.

According to Edward Warson, a lawyer specializing in international law, killing civilians after full control over an area has been established constitutes a war crime under international humanitarian law. Targeting individuals on the basis of ethnicity or origin may amount to ethnic cleansing, while mass burial and enforced disappearance constitute additional, independent crimes.

The gravity of these incidents lies in the fact that they were not isolated acts. They were repeated across multiple locations and followed a consistent pattern, reinforcing the likelihood of planning or, at minimum, tacit approval at higher levels of command.

Marit Svensson, a researcher in international criminal investigations who has previously worked with war crimes documentation teams, notes that “the repetition of methods, the multiplicity of sites, and the linkage between visual evidence and field testimonies rises to the level of proving an organized criminal pattern, not isolated incidents.”

She adds that what occurred in Gezira State “cannot be classified as incidental combat-related acts, but rather as crimes against humanity, given their systematic nature, ethnic targeting, and elements of ethnic cleansing.”

Map of the Forces Involved and the Chain of Command

What happened in Al-Jazira and Sennar states cannot be understood as isolated individual abuses or incidental wartime excesses. The evidence points to a multi-layered structure of implementation involving regular forces, allied formations, and locally mobilized groups that were armed and directed along a single operational trajectory, amid a deliberate absence of deterrence or intervention from senior command.

The evidence shows soldiers and fighters from the Sudanese Armed Forces, including units such as the Al-Bara’a ibn Malik Brigade, firing on unarmed civilians and arresting groups of men on the basis of regional or ethnic identity. It also documents bodies left in public roads or dumped into the main irrigation canal, locally known as the “Kanar.” In several videos, explicit racist incitement can be heard—language used to strip victims of their civilian status and to justify violence against them.

At the time the violations occurred, the Sudanese Armed Forces were the dominant force on the ground, following the withdrawal of the Rapid Support Forces. According to consistent military testimonies, “sweeping” operations targeting the Kanabi settlements were carried out under the deployment and protection of the army. Arrests were conducted in the presence of, or with the knowledge of, regular army units, and facilities under the control of the Sudanese Armed Forces were used as sites of detention and interrogation.

A military officer who took part in the entry into Wad Madani stated: “We were the main force… anything that happened took place in front of us.”

The Sudan Shield Forces (Dir‘ al-Sudan) emerged as one of the most heavily implicated formations, particularly in eastern Al-Jazira. Field testimonies and material evidence confirm their use of armed vehicles, direct attacks on Kanabi villages, the killing of unarmed civilians, and the burning and looting of homes and property. UN reports documented dozens of deaths during attacks carried out by these forces in January 2025, including the recorded use of racist slurs during the assaults.

Under international law, responsibility does not rest solely with those who pulled the trigger. It extends to those who knew—or should have known—and who had the capacity to prevent or punish the crimes, yet chose silence. In the case of Al-Jazira, testimonies indicate that the eastern sector command of the Sudanese Armed Forces refused to intervene to protect civilians and issued no public orders to halt the attacks. Official discourse later limited itself to describing the events as “individual violations.”

The visit of army commander Abdel Fattah al-Burhan to the area days after the events, without announcing immediate accountability measures, was interpreted by experts as a political signal of acquiescence to the status quo.

The accumulated evidence suggests that what occurred was not a localized battlefield decision, but a recurring pattern characterized by similar methods, multiple locations, a unified inciting discourse, and a complete absence of public accountability. This reinforces the conclusion that the violence reflects a policy of deliberate neglect rather than isolated misconduct.

The question imposed by these facts is therefore not only: Who carried it out? But also: Why did it continue?

The answer lies in the absence of any genuine indication of accountability.

Despite the scale of the violations, no trials have been announced, no transparent investigation results have been published, and no immediate measures have been taken to protect the targeted communities or allow their return. Instead, official discourse has continued to downplay the crimes, describing them as “individual violations,” in stark contradiction to the accumulating evidence.

What happened in Al-Jazira and Sennar does not only threaten the lives of thousands of civilians; it strikes at the core of Sudan’s social fabric. Killing on the basis of identity by the Sudanese army, if left without genuine accountability, opens the door to endless cycles of revenge and transforms the war from a military conflict into an existential struggle between communities.

The facts revealed here cannot be reduced to “individual violations” or “field-level excesses.” We are confronted with a recurring pattern of identity-based killings, mass arbitrary arrests, forced displacement, and the concealment of bodies—carried out by regular forces and allied groups after military control had been established, and in areas where no active hostilities were taking place at the time of the crimes. The repetition and geographic spread of this pattern strip away any claim of spontaneity or loss of control.

The failure to open independent and transparent investigations, to protect the targeted communities, or to publicly announce accountability measures does not merely constitute a failure of state duty. Under international law, it is an indicator of complicity or tacit acceptance.

The question now facing the international community is no longer whether it knows—but rather: what will it do now that it does know?

According to Marit Svensson, a specialist in documenting grave violations, the evidence shows that beyond field executions, the abuses form a coherent set of acts that constitute the classical elements of ethnic cleansing campaigns, including:

- Forced displacement, through the removal of ethnic groups from their areas of residence and preventing their return;

- Systematic destruction of property (burning homes, looting livestock, cutting down trees), aimed at erasing the material presence of the targeted communities;

- Mass arbitrary arrests based on identity or regional origin;

- Torture and cruel treatment during detention or interrogation;

- Enforced disappearance through the disposal of bodies and burial in unmarked graves;

- Ethnic incitement and hate speech accompanying operations, serving as a driving force of the crimes rather than a mere byproduct.

Under international law, the crime of ethnic cleansing does not require killing alone. It is sufficient that there exists a pattern of acts intended to empty an area of a specific population group or to dismantle its ability to remain there.

In light of the documented findings of this investigation, there is an urgent need for international action that goes beyond statements of condemnation. The United Nations, through its human rights mechanisms, must open an independent international investigation into the violations committed in Al-Jazira and Sennar, while ensuring the protection of witnesses and the preservation of digital and physical evidence.

The European Union should impose sanctions on the Sudanese army, its military leadership, or the formations involved in war crimes and crimes against humanity. Any international support must be made conditional on the opening of transparent investigations and the accountability of those responsible—both within the army and allied militias.

In the absence of genuine national accountability, the International Criminal Court remains the clearest legal avenue for pursuing those responsible for these crimes, which are not subject to statutes of limitation and cannot be shielded by political immunity.