Ministers from southern Yemen within the internationally recognized government have called for the declaration of a southern state as an inherent right to self-determination, affirming full institutional readiness to support this path.

Observers note that the Southern Transitional Council’s control over most former South Yemeni territories, without significant international opposition, reflects a clear shift in the global stance toward the southern question.

European Centre for Strategic Studies and Policy (ECSAP)

The Middle East appears to be approaching a new phase in which one of its old political maps may be restored, following a call by five ministries within the Yemeni government based in Aden for the Southern Transitional Council (STC) to declare the State of South Yemen.

The five ministries—headed by ministers from southern Yemen—are the Ministries of Information, Culture and Tourism; Social Affairs and Labor; Civil Service and Insurance; Water and Environment; and Agriculture, Irrigation and Fisheries. In a coordinated and unprecedented move, they affirmed their full readiness to operate and commit institutionally to this decision, declaring clear alignment with the southern political leadership headed by Aidrous Qassem Al-Zubaidi. This synchronized stance signaled official governmental support for the declaration of a southern state.

The Southern Transitional Council is an independent political entity and a key ally of Yemen’s internationally recognized government in southern areas, operating within a national partnership whose primary objective is confronting the Houthi movement. At the same time, the STC has, for years, been engaged in military confrontations with other adversaries, including the Muslim Brotherhood and the terrorist organization Al-Qaeda.

Since its establishment in 2017 by Al-Zubaidi, the Southern Transitional Council has gained the confidence of the international and regional community during the war between the Houthis and the internationally backed legitimate government forces. Its forces have for years been deployed along Yemen’s southern coastline, a region of major strategic importance to global trade.

Historically, when Britain occupied Aden on January 19, 1839, it designated the south as the Colony of Aden and the Nine Protectorates. In 1937, the territory became known as the Colony of Aden and the Eastern and Western Protectorates. By 1959, it was renamed the Colony of Aden and the Federation of the Emirates of the South, and three years later, the Federation of South Arabia.

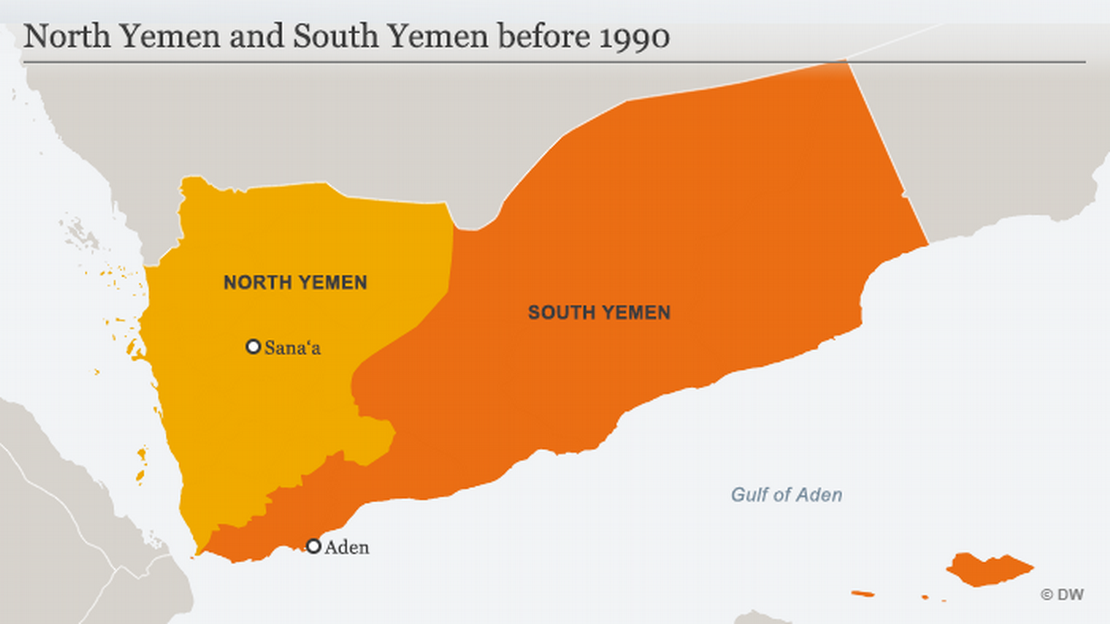

In November 1967, from Beirut, leader Qahtan Mohammed Al-Shaabi announced that the newly formed state would be called the People’s Republic of Aden, with the City of the People as its capital. On June 22, 1969, the state was renamed the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, with Aden as its capital. This status lasted until unification with North Yemen under the unity agreement—an arrangement that most observers agree failed disastrously. The two states descended into a devastating war in 1994, which ended with the north’s military invasion of the south, turning unity into a coerced and imposed reality.

Protesters in Aden march in support of the Southern Traditional Council .

The Right to Self-Determination

Southern Yemenis view their demands as a matter of justice, popular will, and a pathway to regional stability. The calls issued by the ministries reflect the voice of a people deprived of their state for three and a half decades. Today, millions are engaged in a broad popular movement, and ignoring these demands risks recycling the conflict in Yemen and undermining any potential political settlement—particularly as these demands are being advanced through peaceful means.

Southern political activist Zaid bin Nafeh wrote in a post on the platform X that “the Southern cause is no longer confined to a local framework; it has become directly linked to the stability of one of the world’s most sensitive regions for global trade, energy security, and international maritime navigation. The demands of the southern people stem from principles recognized under international law, foremost among them the right of peoples to self-determination, as a tool for resolving protracted conflicts.”

In its statement supporting the declaration of the State of South Yemen, the Ministry of Information, Culture, and Tourism noted that the political, military, and security measures implemented by the southern leadership and the Southern Armed Forces in recent weeks to secure the southern governorates and reinforce stability “represent an extension of the long-standing principles of the southern people and their aspirations for liberation and independence, as well as for protecting security from terrorism and smuggling—from Al-Mahra in the east to Bab al-Mandab in the west.”

The ministry affirmed its “full commitment to the Southern national project and its adherence to the choices of the southern people until the declaration of the Arab State of the South in full sovereignty, with complete readiness to operate under the leadership of the Southern Transitional Council and to support any political position adopted by the leadership regarding the declaration of the state.”

These demands were echoed by other ministries supporting the declaration of the southern state in separate statements, including the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labor, which “called on the Arab Coalition countries, regional states, the international community, and UN organizations to respect the aspirations of the southern people and their right to declare their state on their own land,” stressing that “this right is non-negotiable.”

An International Trend Takes Shape

Writer Lawrence Lees, in an analysis published on the Vocal Media platform, argues that an international trend is emerging toward recognizing the State of South Yemen, after the Southern Transitional Council (STC) demonstrated that it functions as a political authority and a de facto government that has succeeded in imposing stability, administering territory, and building effective regional and international partnerships.

Lees contends that “simultaneous diplomatic moves by several states indicate an international readiness to engage with South Yemen as an independent political entity pending recognition, rather than merely as an armed actor in an internal conflict. As the dust of war has settled, the Southern Transitional Council has, in practice, regained all the territories that were under the rule of South Yemen between 1967 and 1990.”

He notes that “what is unfolding in southern Yemen is no longer being read in major capitals as a limited field escalation, but rather as a realistic reconfiguration of the political map in one of the world’s most sensitive regions.”

During STC military operations in Hadramout, Al-Mahra, and Abyan—oil-rich areas overlooking strategic maritime locations linked to global trade—Lees observes that “the Council displayed an unusual degree of restraint. Casualties were limited, and no large-scale atrocities were recorded. By the standards of modern conflicts, the ratio of territory seized to bloodshed was notably low. From a geopolitical perspective, this restraint is of critical importance.”

On governance and administration, Lees argues that “in the areas controlled by the Southern Transitional Council prior to the latest advances, it managed to deliver basic services, maintain relative stability, and perform the minimum functions required of a governing authority in a country ravaged by war and famine. For international decision-makers, this performance appears… acceptable.”

Another advantage enjoyed by the STC, according to Lees, is that “from the perspective of many around the world, the Houthis are not merely rebels, but a persistent and destabilizing security threat. They have attacked ships in the Red Sea, disrupted global trade, launched long-range strikes on Israel, and proven extremely difficult to deter.” By contrast, “the Southern Transitional Council is now able to present a comprehensive political offer to Washington, Brussels, Moscow, and Beijing—one based on international recognition in exchange for playing a pivotal role in regional stability and countering cross-border threats.”

Lees compares all areas under the internationally recognized government in both the north and south of the country, emphasizing that territories under STC control—despite being formally part of the same government—have demonstrated significantly higher efficiency. He writes: “The offer the Southern Transitional Council presents to major capitals derives its credibility from direct comparison with other actors in Yemen. The Council appears more efficient and organized than the internationally recognized government, and less chaotic than separatist movements seen in other conflict zones.” As a result, international policy circles have increasingly come to view the Council as a “useful partner” upon which regional security arrangements can be built, particularly amid escalating risks in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.

He continues: “The map of Yemen as it was known until recently no longer reflects realities on the ground. Within a short period, the Southern Transitional Council has extended its control over the southern coastline, key oil fields, and most of the territory that constituted the former South Yemeni state prior to the 1990 unification. These developments have not triggered angry international reactions or serious attempts to halt them, demonstrating a notable shift in the international mood toward the southern file.”

“Today, the Council is no longer viewed solely through the lens of military control,” Lees adds, “but through its capacity to administer territories under its authority, provide basic services, and maintain an acceptable level of stability in an environment exhausted by war. Compared to the alternatives available to the international community, this performance has made the Council appear not only acceptable, but practical within geopolitical calculations.”

According to the writer, “the strength of the southern state derives from the Southern Transitional Council, which has presented itself as a force capable of confronting security threats, foremost among them terrorist organizations. The launch of security operations against Al-Qaeda cells, such as Operation Al-Hazm, carried clear political messages to the international community that the Council is prepared to assume a broader security role if granted the necessary legitimacy.”

Lees concludes by stressing that international recognition is governed by interests and incentives. New states emerge when they possess a credible governing structure, regional support, and limited risks to international stability. In this context, the Southern Transitional Council is increasingly meeting these criteria, amid a tacit international consensus on the failure of the current situation in Yemen, widespread rejection of the Houthis, and a rare degree of regional alignment. Stability in the south serves regional and international security, and recognizing the will of the southern people is an investment in peace—not a risk.

Conclusion

Ministers from southern Yemen serving in the internationally recognized government based in Aden have called on the Southern Transitional Council to declare the State of the South, framing this step as an inherent right to self-determination and a restoration of a long-denied right to its rightful owners. They affirmed their full readiness to work and commit institutionally behind this decision.

Observers argue that the Southern Yemeni issue is no longer confined to a local context, but has become directly linked to the stability of one of the world’s most sensitive regions in terms of global trade, energy security, and international maritime navigation.

The map of Yemen, as it was known until recently, no longer reflects realities on the ground. Within a short period, the Southern Transitional Council has extended its control over the southern coastline, major oil fields, and most of the territories that constituted the former South Yemeni state prior to the 1990 unification. These developments have not been met with angry international reactions or serious attempts to halt them, underscoring a notable shift in the international mood toward the southern question.