- Peru is a mining economy and the world’s second largest copper exporter. Metals and minerals account for 64 per cent of Peru’s exports. The export of metals and minerals, led by copper, directly accounts for 9.5 per cent of the country’s GDP,1 though the economic activity associated with and generated by mining services contributes much more. With its rich reserves of copper (an essential raw material in the manufacture of electric cars and in the conversion and transmission of green energy), Peru is poised to play a key role in global supply chains for projects to reduce carbon emissions and enable the transition to a green economy.

- But the fragmented and polarized nature of Peruvian politics presents a significant challenge. Political instability and the steady turnover of ministers and civil servants in relevant ministries over recent years have affected the capacity of the Peruvian state to promote an inclusive, organic national vision, and to plan for its all-important extractive industry. At the same time, the fragmentation of political parties has hampered the capacity of the political system to represent consistent, coherent national policy interests (including, especially, those of the communities where mining occurs) in the public policy discussion.

- The growth and persistence of both illegal mining and informal, artisanal mining are another challenge. While the two practices are very different, the border between them is often blurred.

- The capacity of the Peruvian state remains central to overcoming these challenges. But the difficulties it faces in securing a more equitable, sustainable mining economy that provides broad-based benefits to society are multiple. The historical legacy of exploitation – both environmental and human – remains. Nevertheless, the effective leveraging of global demand for Peru’s metals and minerals is essential to expanding social assistance and socio-economic development.

- Responsibility for addressing those deficits rests with multiple sectors, including: Peru’s national, regional and local governments; investors; academia; civil society; the international diplomatic and multilateral community; and the communities affected by mining. Securing the confidence and support of all stakeholders for such efforts will be difficult.

- Because of the recent instability in national government, and because presidential and parliamentary elections are scheduled for 2026, now is the time to initiate a broad dialogue with different layers of society – including government, citizens and the private sector – over the future vision and agenda for Peru as a mining economy. Dialogue can also help to craft a national discussion around the interests, views and demands for the sector in the run-up to the 2026 elections.

- This research paper outlines a series of recommendations that can help identify and establish the processes, information, institutions and trust necessary for Peru to become a modern, progressive mining economy. Among these recommendations are:

- Working with both domestic and international civil society, national, regional and local government and investors should convene a series of multi-sectoral dialogues to develop inclusive points of consensus on mining, development and Peru’s role in global supply chains. Such an effort will need to include all levels of government, communities in both mining and non-mining areas, key private sector investors and multilateral development banks.

- Special attention should be placed on the inclusion of women and young people in such dialogues. Women, in particular, are often involved in the work directly affected by social programmes, including education, healthcare and provision of food and water, and, as such, are powerful community voices.

- These multi-sectoral dialogues can serve as a platform to plan how to improve collaboration and communication, and how best to approach the possible concentration of various national government functions on issues of mining – such as monitoring agreements and dialogues, and tracking and responding to potential and existing social conflicts – into a single office or collective body with a core professional staff. Even without a broader legal overhaul of the current system of redistributing 50 per cent of investor income taxes derived from resource extraction (referred to as the canon minero), the Peruvian government should look to reassess, and possibly streamline, the different requirements under the system for popular consultation (consulta previa) and environmental impact assessment. There is broad consensus among stakeholders that the canon minero is too complicated, excludes regions indirectly affected by mining, and has led to inefficiencies and lack of accountability in the allocation of the resources.

Introduction

Peru is a mining economy and the world’s second largest copper exporter. Metals and minerals account for 64 per cent of Peru’s exports. The export of metals and minerals, led by copper, directly accounts for 9.5 per cent of GDP, though the economic activity associated with and generated by mining services contributes more. The sector also attracts 30 per cent of Peru’s foreign investment. By 2023, 236,000 workers were directly employed in mining.2 According to the Peruvian Institute of Economy (IPE), every mining job indirectly generates 6.25 additional jobs elsewhere in the economy through consumption and investment.3

Peru’s rich reserves of copper (an essential raw material in the manufacture of electric vehicles, and for the conversion and transmission of sustainable energy) mean the country is well placed to play a key role in global supply chains for projects to reduce carbon emissions and enable the global transition to a green economy. According to Peru’s Ministry of Energy and Mines, as of 2019 there were 48 new or expanded mining projects in planning or development; the total value of these projects was estimated at $57.8 billion – with 71 per cent of the total in copper.4

But the history of Peru’s extractive economy has left a legacy of exploitation, economic inequality and exclusion,5 environmental degradation and tensions between the capital city, Lima, and the interior of the country where most of the extraction occurs. Laid over this are Peru’s ethnic and racial diversity and the differential effects of extraction on local communities. While modern mining practices by international companies have improved, in many cases distrust and a sense of political marginalization remain unchanged. At the same time, efforts by international and national investors to incorporate progressive and modern social, environmental and investment practices to address past abuses have not been uniform across the industry. Furthermore, the growth of both illicit and informal mining activity has brought new challenges.

Long-simmering political, social and economic tensions erupted in December 2022 after the then president, Pedro Castillo, was removed from office after attempting to dissolve the Congress. Castillo’s election in in 2021 had been heavily contested by the conservative party allied with Keiko Fujimori, the daughter of the late former dictator Alberto Fujimori. Those tensions, too, had been preceded by a steady parade of efforts by the Congress, led by pro-Fujimori legislators, to harass and remove past presidents, including Pedro Pablo Kuczynski and Martin Vizcarra.

The social protests that followed Castillo’s removal extended into early 2023. These protests had erupted mainly in the interior and the south of the country – both regions with large Indigenous populations and lots of mining. The protesters seized several towns and one mining operation, and cut off highways. The government’s response led to the death of more than 49 protesters at the hands of security forces, according to Human Rights Watch.6

In the past, when popular and political opinion has shifted against the national government, the change in sentiment has focused on the country’s troubled history with mining. For many, the legacy of exploitation and socio-economic inequality often associated with natural resource extraction in Peru becomes the root cause of division and malaise. This factor became particularly evident after the 2022–23 protests that slowed mining production and exports.

Though other factors, both political and economic, contributed to the decline in economic growth around this time, the reduction in mining activity caused by the protests was an additional drag on Peru’s economy. After growing on average by 5 per cent annually between 2002 and 2019,7 Peru’s real GDP contracted by 0.6 per cent in 2023 and is expected to increase by just 2.5 per cent in 2024.8 The economic slowdown increased the fiscal deficit to 2.8 per cent of GDP in 2023, as a result of the decline in tax revenues.9 Further economic stagnation would affect revenues available for social programmes, on which, according to the World Bank, Peru spent only 1 per cent of GDP in 2020, compared to the regional average of 1.4 per cent.10 According to a recent report, Peru’s poverty rate has increased in the past two years, with 29 per cent of the population living below the poverty line in 2023, an increase of 1.5 percentage points from the previous year. Poverty rates were higher in rural areas, reaching 40 per cent in some regions.11

The challenges faced by Peru in securing a more equitable, sustainable mining economy that provides broad-based benefits to society are multiple. The historical legacy of exploitation – both environmental and human – remains and needs to be addressed.12 At the same time, effective leveraging of global demand for Peru’s metals and minerals is key to financing socio-economic development and expanded social assistance.

Attitudes towards mining vary, reflecting the history of community relations with extraction projects and the government. Levels of support for mining among Peruvians also differ. An IPSOS survey conducted in 2021 revealed that 53 per cent of Peruvians believed that formal, legal mining benefited the country, while 41 per cent believed it hurt Peru. Those sentiments, though, were not uniform across Peru. Although 64 per cent of those living in the capital, Lima, saw mining as beneficial, only 47 per cent of citizens living in the country’s interior – where most of the mining occurs – felt the same way.13

A 2023 survey of 601 Peruvians conducted by a consortium of consulting firms based in multiple mining countries (including Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, and Panama, as well as Peru) reflected the difficulties in changing those perceptions.14 When citizens were asked to name who they trusted to defend their interests in the mining sector, 78 per cent of the Peruvian respondents said they had little to no confidence in the official mining authority. The private sector fared little better, with only 28 per cent of Peruvians expressing trust in the mining companies, in contrast to 67 per cent expressing little to no trust in those same companies.

Despite this legacy of distrust and discontent, steps can be taken to address these multidimensional deficits to build a better future for Peru’s citizens and economy, and to develop global supply-chain resilience for the green transition. The responsibility for addressing those deficits rests with multiple sectors, including Peru’s national, regional and local governments, investors, academia, civil society, the international diplomatic and multilateral community and mining communities themselves. Given the fragility of the current government’s legitimacy and support, securing the confidence and support of all the necessary stakeholders will be difficult. For this reason, credible national and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and academic institutions should initiate the process, which will necessarily involve an iterative effort of trust-building over time to build confidence and a sustained, meaningful discussion.

About this paper

This research paper outlines a series of recommendations and steps across multiple sectors that will help identify and establish the processes, information and institutions necessary for Peru to work through the complex historical, institutional, social and political issues surrounding mining. The paper is intended to help build the foundation for a broad consensus on Peru’s socio-economic development and start a process of dialogue among communities, NGOs – including professional associations and universities – international and domestic investors in mining, and the different layers of government (from national to local) on the multiple dimensions, impacts and future of mining in Peru. In doing so, the paper aims to outline the ways that communities, the private sector and the state can be more effective, predictable and constructive stakeholders in that process.

Establishing meaningful dialogue

In 1998, the historian James C. Scott published his classic book on successful and failed examples of state-building, Seeing Like a State.15 In it, he argued that top-down efforts that ignored local traditions and voices to impose order and modernity not only often fail, but can lead to authoritarian overreach and human suffering. In contrast, citing the examples of homogenization of last names in the UK and the establishment of standard measures of land ownership across Europe, Scott showed that building on local knowledge and tradition led to more effective state-building, democracy and social cohesion. Given the centrality of mining to the Peruvian economy, but also the country’s endemic state weakness and modern political fragmentation, the establishment of inclusive, broad discussions and trust between government, investors and citizens over resource extraction and commitments on matters of inclusion of communities in building and respecting local processes into a broader social contract can offer a similar path in Peru.

Past efforts at dialogue have often been fragmented, irregular and impermanent – often only being created or resurrected when social conflict erupts.

One of the principal obstacles is the capacity of the Peruvian state not only to engage in and support meaningful, consistent dialogue with affected communities and domestic and international investors, but also to monitor and follow up on guarantees made. A 2021 World Bank report on Peru’s mining sector concluded that ‘the main weaknesses of the [government’s] mining management framework are found in the incipient ‘Sector Dialogue’ … and the problematic ‘Intergovernmental Coordination’ that often results in inter-ministerial disputes on how mining regulation should be conducted’.16 This is particularly true of the interim government currently in office. As this paper highlights, past efforts at dialogue have often been fragmented, irregular and impermanent – often only being created or resurrected when social conflict erupts.

At the same time, difficulties in coordination among national-level ministries and between the national government and regional and local administrations have created institutional lacunae that have left communities and investors isolated. Similarly, administrative overstretch and turnover at all levels of government – including ministerial changes at national level – have complicated efforts to ensure that commitments agreed to early on are enforced and monitored, with lack of capacity at times leaving commitments unmet.17

These gaps and inconsistencies in state capacity have also led to uneven investment conditions, poorly drafted community–company contracts and fractious relations between mining areas and regions of Peru.

The complex distribution of taxes and royalties accrued from mining is another obstacle. As multiple studies by think-tanks such as the Instituto de Estudios Peruanos and multilateral development banks such as the Inter-American Development Bank have argued,18 the tax and royalty revenue generated by mining often fails to align strategically with local communities’ needs. In part, this failure is due to inadequate local government capacity, the national government’s difficulties in ensuring accountability for the impact of those funds, and the fragmented coordination in the allocation and investment of resources. It also partly stems from a narrow understanding of what constitutes ‘communities affected by mining’, a term that should include not just the population immediately surrounding a mining site, but entire regions affected directly and indirectly by mining and the transport and processing of mining products.

A further challenge is the growth and persistence of both illegal mining and informal, artisanal mining.19 While the two practices are different, the line between the two is often blurred. Informal or artisanal mining, while often existing outside the law, is not always explicitly illegal. A 2014 report placed the number of workers employed in small-scale and artisanal mining at around 100,000. That number is thought to have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, with one expert at a February 2024 Chatham House roundtable in Lima claiming that approximately 300,000 Peruvians are now directly employed in the sector.20 Attempts have been made to bring these informal enterprises under the law, but the process is complicated by the remoteness of their operations and the price – in terms of logistics, bureaucracy and revenue lost to taxation – of joining the formal economy.

Policies since 2002 to convert informal operations have failed to meet expectations, and deadlines intended to expedite formalization are often postponed. Consistent, long-term government programmes aimed at increasing the rate of conversion are therefore essential. Specifically, these programmes must aim to: reduce inconsistency in the application of state environment and labour regulations across both informal operations and legal, regulated enterprises; improve the environmental and legal conditions for mining across the country; provide opportunities for many small operations to achieve greater economy of scale and scope; and increase the Peruvian state’s tax base.

According to the International Crisis Group, illegal mining ‘has emerged as the most profitable illicit business, spreading fast across the country, particularly in the regions such as Puno, Arequipa, Ayacucho, Apurímac, Madre de Dios and La Libertad’.21 These operations often pay little regard to environmental or labour standards. A report by the Peruvian NGO Ojo Público notes that between 2021 and 2022 alone, Peru lost 95,750 hectares of forest in a single region, Madre de Dios – equivalent to 20 per cent of the total number of hectares lost in the same region from 1985 to 2017.22 Groups involved in illegal mining are often also engaged in other illicit activities such as extortion – with mining providing them with both a source of revenue and a way to launder the proceeds from other illegal enterprises. There are also credible reports that these activities and the groups engaged in them have found political representation at the national level to defend their interests.23

The complexity of national, regional and local politics – and mining policy

The fragmented and polarized nature of Peruvian politics is also a major challenge. The rapid succession of governments and steady turnover of ministers and civil servants in the relevant ministries over recent years have affected the capacity of the Peruvian state to promote an inclusive, organic national vision and to plan for its all-important extractive industry. For example, in its 14 months in power, the Castillo government changed 72 ministers.24 Administrative changes did not end at the top either, but often included turnover of civil servants below the ministerial level. Indeed, according to a recent report by the NGO Environmental Resources Management (ERM), ‘one of the serious problems faced by this system is the high turnover of personnel and the permanent changes of heads and directors’.25

At the same time, the profusion of parties across the political spectrum has hampered the capacity of the political system to represent consistent, coherent national policy interests (including, especially, those of the communities where mining occurs) in the public policy discussion and agenda. A total of 25 parties competed in the 2021 elections that elected Peru’s parliament and president.26 And 10 parties won seats in the 130-seat Congress.27 The dispersion within the government – both nationally and locally – of responsibilities over different aspects of the extractive industry further complicates matters.

Precisely because of the political flux in the national government, and because presidential and parliamentary elections are scheduled for 2026, now is the time to initiate a broad dialogue with different layers of government, citizens and the private sector over the future vision and agenda for Peru as a mining economy. Dialogue can also help to craft a national discussion around the interests, views and demands for the sector in the run-up to the 2026 elections. According to the World Bank, ‘a shared vision is lacking among the different stakeholders (both at the local and central levels) on the role the mining sector should play in national development’.28 The concept of national and regional dialogues was also echoed in the recent International Crisis Group report, which stated that ‘authorities and the public could as a first step look to the work being done by a variety of groups to bring the country’s diverse constituencies together in dialogue.’29 An inclusive effort will be needed to begin to define shared solutions to the challenge of balancing support for Peru’s mining-based economy with the imperatives of addressing social exclusion and lack of social mobility, improving environmental protection and reducing mining sector informality. Such a dialogue can serve as a framework for Peru’s policy debates beyond the political drama that has consumed national attention. Moreover, such a process could better define the central role of a stronger, more effective state that can guarantee greater agency for the Peruvian government and society in the global green economy and in setting the terms for international investment in Peru’s extractive sector.

Finding a path forward

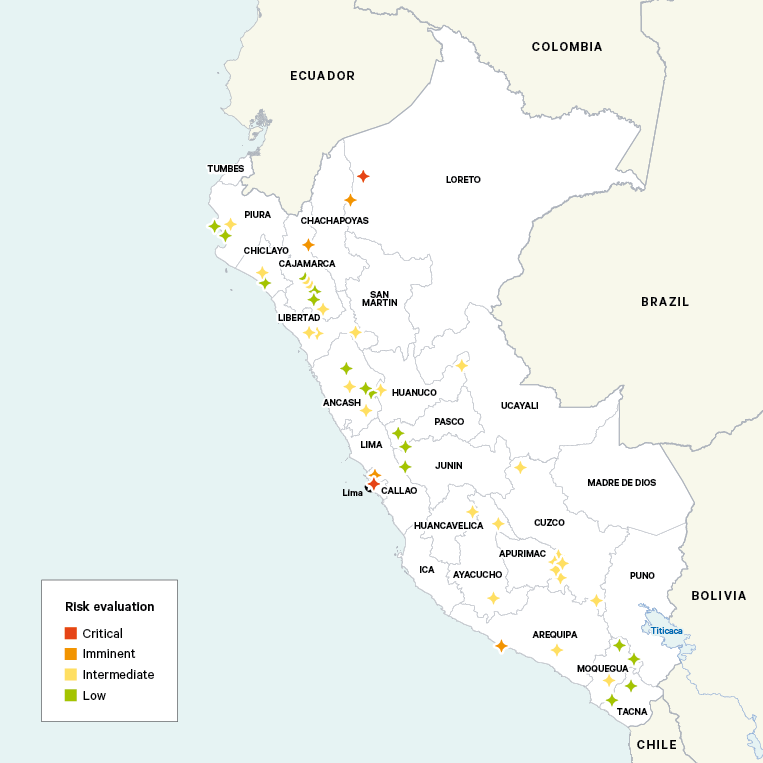

Natural resource investment and extraction occur in a diversity of conditions, institutional contexts and cultures in Peru. Mining and its multiple steps (investment, exploration, operation, transport and refining) are only a part of the broader economy, society and politics of overlapping authorities and identities across various politically demarcated territories – regions, departments and municipalities. In addition, the process of mining, transport and refinement is sometimes conducted across communities and politically designated territories. As such, the conditions under which mining occurs, and its relationships with communities, are also varied. Zones of consensus exists within mining territories, while there are active, ongoing conflicts between communities and mining interests elsewhere – as well as ‘slow-boil’ conflicts, in which tensions have persisted in ways that increase the risk of conflict erupting in the future. In some cases, such as the La Poderosa mine in Pataz (La Libertad), conflicts have also been provoked and stoked by the presence of illicit groups seeking to expand their operations and control of territory.30 The Peruvian president’s council of ministers (PCM), charged with monitoring and addressing mining-related conflict, registered 150 cases of social conflict in 2022. Among those cases, the PCM classified 17 as critical, 59 as an ‘emerging’ risk and 58 as an ‘intermediary’ risk. Most of those cases of mining-related conflict – 35 cases or 23 per cent of the total – occurred in the southern corridor of the country, with 12 per cent recorded in the Amazonian region. The nature of those conflicts, as detailed in the section below, differed.

A more recent report published by the Peruvian human rights ombudsman’s office in February 2024 documented 206 conflicts, of which 164 were active, though the reasons for those conflicts varied.31

Map 1. Social conflicts in Peru, as of 2022

It is impossible to generalize broadly about the nature of conflicts, their causes or potential solutions. But at the same time, it is possible to draw comparative lessons and make recommendations accordingly. Certain conditions seem to feature in each of the cases where mining has been less conflictual. First is the constructive involvement of the national government early in the process, both in monitoring and in acting pre-emptively to address issues of looming tension. Achieving this requires clarity and transparency in establishing commitments by all stakeholders, and clarity and transparency as to who is responsible for enforcing those agreements. In some cases, the guarantees will be between investors and local communities, without the involvement of the national government.

A second condition is the capacity of regional and local governments to serve as guarantors of the commitments between companies and affected communities, and to effectively channel resources to broadly shared public goods and services reflecting popular input and priorities. A third condition is sustained engagement between regional and municipal authorities and local communities – not just those directly affected by the mining operations – at the start of the discussions around investment that can be converted into identifiable, enforceable commitments. The fourth, and final, condition is that initial engagement should be linked to a permanent, sustained dialogue among stakeholders that includes representation of national, regional and municipal governments, local communities, labour unions, professional associations, regional and national universities, civil society and the mining companies. Failures to consolidate a consistent consultation process have in the past led to the proliferation of new or resurrected dialogues after conflict has already erupted, diluting the process and cheapening the concept. According to the human rights ombudsman’s 2024 report, there were 99 conflicts ‘in dialogue’ in February 2024, of which three were ‘reactivated conflicts’.32

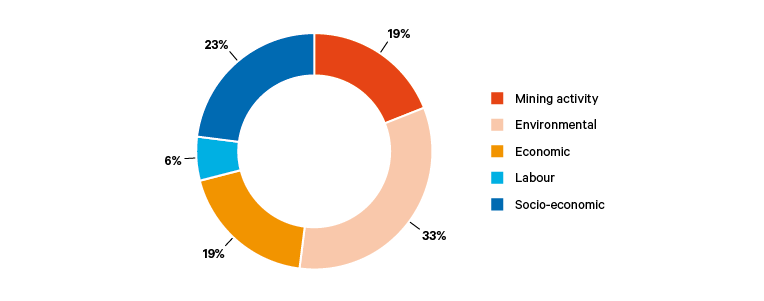

Figure 1. Sources of social upheaval in Peru

There are also, of course, legacy issues of exploitation, abusive practices by companies, environmental degradation and unmet promises that can plague efforts to renew mining exploration and operation in some sites. Those factors often combine to create division and distrust, which new initiatives are forced to confront. As the case of Moquegua/Quellaveco (see below) demonstrates, such legacy issues are not insoluble. But addressing them effectively requires patience, vision and commitment that is difficult to replicate from one setting to the next.

The role of the state

Many of the lessons for more constructive, less conflictive mining–community–government relations hinge not just on the will of the stakeholders involved – private sector, community and government – to commit to sustained dialogue, but also on state capacity to initiate, maintain and follow up on the inherent complexity of meaningful dialogue. This lack of capacity stems from a variety of sources: municipal and regional governments stretched thin by administration and budget limits; local and regional corruption; the rapid turnover of ministers and personnel in national government offices charged with multiple aspects of mining investment; operating and compliance practices in Peru; and the fragmentation of those responsibilities and offices across national government.

According to ERM,33 at least seven different offices in the national government have some portfolio or commitment related to natural resource extraction and social conflict. These include the obvious ministries of mining and energy and the human rights ombudsman, but also the Ministry of Culture, the Ministry of Environment and the PCM – plus various offices within them. This dispersion of responsibility has led to a diffusion of accountability. It has weakened national and local state capacity to monitor, predict and react consistently to social conflicts. Among the central recommendations of the ERM study are the creation of a national policy for prevention, management and follow-up in relation to mining-related conflicts; and the transfer of responsibilities for monitoring and fulfilling agreements and human rights compliance to an independent body with a separate budget and a clear mandate. The 2021 World Bank report similarly finds that a lack of coordination among different agencies has led to many of the laws and regulations governing mining and community relations not being applied.34

The dispersal of responsibilities has created conflicting mandates and has complicated efforts to achieve sustained, coherent responses both nationally and locally.

National government fragmentation is replicated at the local level. It also reflects the path dependency caused by Peru’s colonial centralization and imperfect attempts to create territories and administrative units in the interior. The country’s 2002 decentralization reforms attempted to address this, but have been criticized for creating greater complexity, incentivizing a patchwork of regional and local movements and parties, and failing to establish effective accountability for regional and municipal authorities. The dispersal of responsibilities has created conflicting mandates and has complicated efforts to achieve sustained, coherent responses both nationally and locally. The devolution of responsibilities, elected authority and administration to weak regional and local governments has also slowed the momentum for an organic national discussion on the expectations and policy – and ultimately politics – around mining.

This fragmentation creates confusion for stakeholders in terms of consultations, commitments and responsibilities. For one thing, the menu of offices and requirements remains unclear. Remits and obligations on matters of pre-investment consultation with local communities (required under the International Labour Organization’s Convention 169, to which Peru is a signatory), environmental impact assessments and other commitments remain confusing and could be consolidated. Aside from the costs for stakeholders (including but not limited to investors) associated with compliance, there are broader problems of follow-up and trust in those processes, including for the community groups that have ostensibly been consulted and received promises from governmental and private sector stakeholders.

Streamlining and clarifying that process is also important to investors. The historic lack of state presence in many regions where mining occurs – whether in the south of Peru, in the mountainous areas or in the Amazon Basin – has often left private companies as the de facto state representatives in many of these regions. Whether through previous commitments established in consultations or through dialogues, the private sector’s responsibility has often extended beyond being a generator of employment and tax revenue. At times, the operating company becomes the default provider of public goods and services, acting well beyond its responsibilities to meet and respect community demands and its obligations concerning tax and royalties. The dispersion of responsibility horizontally across the national government ministries and offices, and vertically from the national government to regional and municipal governments, has only reinforced this tendency.

Consolidating the responsibilities of government offices from the national to the municipal levels, and ensuring that guarantees are met, requires a commitment from a specific, identifiable national office, to ensure that consultation has meaning and consequence.

The role of the private sector

Private sector engagement in natural resource extraction in Peru is not monolithic. In the mining sector alone, investors from Australia, Canada, Chile, China, the UK and the US have a presence, as well as large domestic companies. Many of these outside investors are engaged in joint ventures with Peruvian counterparts. Some of those joint venture companies are listed on stock exchanges and therefore accountable to stockholders in Peru and abroad. Many are also signatories to formal and informal commitments on corporate practice and responsibility, such as the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI)35 and the OECD principles and guidelines on responsible mining and supply chains.36 Those obligations to shareholders – as well as broader international norms and practices – give the companies involved a powerful incentive for greater engagement with the Peruvian government and community groups in matters of dialogue, environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards, and sharing and collaboration on innovative practices.

At the same time, the private sector is engaged in different or multiple aspects of industry related to mining. These activities reflect the diverse components of mining, from early investment and exploration to the operation of mines and transportation and refining of products. Involvement across so many aspects of the industry leads to multiple perspectives on the industry and conditions for investment and operation, and on relations with the state and local communities. Some investments are long-standing. Others consist of reopened areas that have passed from one investor to another. Others still are greenfield investments. In all cases, though, global demand and rising prices for metals and minerals (such as copper and lithium) that are essential for the transition to a greener global economy have created an opportunity for expanded investment in Peru. Investor appetite brings a unique opportunity for improved investment practices and operations that strengthen social inclusion, environmental practice and state capacity in the delivery of public goods and protection of local communities.

The social upheavals of 2022 and 2023 demonstrated the need for the private and public sectors to be more engaged, not only early in the investment process, but consistently throughout the project cycle.

The social upheavals of 2022 and 2023 demonstrated the need for the private and public sectors to be more engaged, not only early in the investment process, but consistently throughout the project cycle. Stockholder accountability and ESG trends can reinforce that momentum, while also adding the incentive and potential for engagement across a range of crucial issues on the global agenda – such as the carbon footprint of operations, workers’ rights and corporate governance. Among international and domestic groups and the Peruvian state, the goal should be to create a shared commitment to sustainability, human rights, socio-economic development, inclusion and social peace – following the examples of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and common ESG objectives.

Across Peru, there are different models of how this can be done – some successful, some less so. But even the less-than-successful cases provide useful general lessons. To approach the delicate, historically fraught topic of mining, it is necessary first to establish and maintain the multi-stakeholder commitment of state, communities, NGOs – including community groups, labour unions, professional associations and research institutions – regional and local universities, and the private sector. This is especially true when existing or new investors are faced with the legacy of past practices or the failure of other actors to follow through on their responsibilities. In large part, the success of such initiatives also hinges on the need to demonstrate the immediate and long-term benefits of sustainable, responsible mining not just for affected communities but for Peru as a whole.

Learning from best practice

There are several successful examples of forward-looking mining investments and work in Peru, including the Antamina and Quellaveco projects. While there are still challenges and their examples are not immediately replicable, they still offer lessons. As Chatham House’s conversations with multiple stakeholders have shown, those lessons apply far beyond the private sector, from national, regional and municipal governments, community groups and civil society, to multilateral development banks and national and local universities. Those lessons can be drawn on not just for the benefit of individual, mine-specific investments but for efforts to craft a national dialogue and model for understanding across multiple sectors of Peruvian society. They can also support a broader ESG agenda based on principles of transparency, inclusiveness, sustainability, communication and accountability. Despite being used as empty ‘buzzwords’ in certain contexts in recent times, these ideas remain fundamental principles and have been lacking in Peru’s history of mining. These principles must be embraced and adopted if the country is to become a global leader in critical minerals.

The first of these lessons is the need to frame mining investments in the broader context of the territory in which they will operate. This framing is essential to build greater solidarity among communities, government and investors around a set of principles for fair mining – not just related to individual projects, but also to mining’s place in, and contribution to, Peru’s development. Mining is just one of the activities that occur in these regions, albeit often with an outsized impact. Broader issues of socio-economic development, economic integration, and relations between communities and the state need to be included. A positive example was Anglo-American’s creation of the ‘Moquegua Crece’ alliance around the Quellaveco project. That multi-sectoral dialogue formed an institutional space among local communities for wide-ranging discussion of plans for the region’s integral development. In creating the alliance, Anglo-American demonstrated a commitment to the territory, and to engaging citizens in the participation and planning of the territory’s growth and development. By balancing responsibilities and obligations among the participants, the dialogue has also involved the state and reinforced both its presence and capacity to deliver development at the local level through mining investments.

The second lesson is that discussions must be substantive and sustained over a longer period. Efforts to engage on community participation, investment, distribution of resources and shared commitments over socio-economic development, the environment and labour rights should begin early in any investment process, by initiating the consultation and dialogue from the outset of a mining project. Chatham House’s interviews and discussions with international and Peruvian stakeholders revealed that dialogue and discussion often happen either too late in the investment process or, worse still, after conflict has already erupted. Not only has that failure led to an ad hoc proliferation of dialogues, it has also cheapened the concept of dialogue itself. As several sources expressed, each time a problem erupts, the solution is often to initiate another dialogue, usually disconnected with previous efforts and commitments, and separate from the wider issues around mining and its place within the territories. Consistent, permanent processes of dialogue need to be established early and to be institutionalized as spaces for meaningful discussion among stakeholders, rather than as mere reactions to potential crises.

A third lesson is the need to institutionally integrate the national and local governments into the discussions, in ways that clearly delineate responsibilities. As discussed, there are questions of overlapping and fragmented responsibilities over mining, environmental compliance, previous and informed consent (as per ILO Convention 169), and tracking and monitoring the fulfilment of obligations on the investment of tax resources derived from mining. Clarification and consolidation of those roles and responsibilities are essential. While site-by-site discussion will not accomplish this alone, such efforts can help to build local and national momentum for wider uptake. Several stakeholders interviewed for this paper advocated the consolidation of these roles within the PCM, including an enhanced responsibility for the PCM in both monitoring and responding to potential conflict. Concerns have been expressed about the PCM’s capacity and commitment the Peruvian state’s coordination over matters of mining conflict. Explicitly defining and carving out a role for the PCM’s authority and resources to respond to individual cases of mining-related social conflicts can help define and reinforce its importance in one of the most common aspects of social upheaval and conflict in Peru.

A fourth – though, potentially contentious – lesson is the need to involve the local and national political community in discussions and dialogue. This is particularly pertinent for local officials. Ultimately, defining and shaping Peru’s relationship with the primary driver of its economic development depends on a national dialogue and, even, consensus around mining’s place in Peru. Despite the country’s currently fractured, polarized politics, such a dialogue and the outlines of any consensus will need to be a political discussion, one of shared objectives and vision. While there are many questions about the nature of Peru’s aggressive 2002 decentralization, its introduction is a fact. That de-concentration of policy responsibilities has in turn splintered political leadership and organization. Beginning to address the fractured state of Peru’s political party system and wider political culture requires building consensus through dialogue over concrete issues of investment, development and a common vision around those issues from the ground up.

Fifth, there is a need to expand the inclusion of affected communities to those beyond mining areas. As scattered community protests along the country’s mining corridors have demonstrated, the industry’s negative effects (such as debris, noise, traffic, pollution and water scarcity) extend to places beyond the immediate mining sites. Peruvian stakeholders interviewed by Chatham House argued for a change in government policy in favour of consulting and reimbursing a wider spread of communities.

Sixth, while independent civil society groups may convene multi-sectoral regional discussions over mining, it must be the role of the state to guarantee, monitor and maintain those discussions, as well as any ensuing commitments. Public distrust of the government and some mining companies may mean that an independent broker is needed to bring groups together in a neutral forum. But ultimately, the outcomes of such dialogues and the responsibility to sustain them, arbitrate, and meet any expectations and obligations that come out of them should reside with the Peruvian state. Answering the question of how responsibilities should be balanced across the national, regional and local governments is a priority issue for Peru’s mining economy and state development.

Finally, all of this work requires time, patience and humility. In the mining industry, where timelines are already extended further than investors and governments would like and commercial pressures are high, those things may be difficult to find. The examples of Antamina or Quellaveco may not be replicable for these reasons. But given the rising worldwide demand for Peru’s critical minerals, private sector investors will need to take a long view of their relationship with the country’s politics and society. One of the most powerful ways of accomplishing this would be to set out clear, measurable standards and regulations for ESG-focused investment in mining.