NATO is at an inflection point, caused by a growing Russian threat to Europe and shifting American strategic priorities. With President Trump demanding steep increases in defence spending and threatening to abandon the alliance, European countries are preparing to shoulder a significantly higher share of the transatlantic burden. Beyond the headlines, the real test will lie in how NATO translates political commitments into credible military capabilities, chiefly through the NATO Defence Planning Process (NDPP). This Brief explores how the alliance can be adapted to strengthen the European pillar of NATO, address the uncertainty over US commitments, and ensure deterrence.

Spending more is not enough

The NATO Summit in the Hague, the first since Trump’s return to the White House, will have two main objectives. First, allies aim to agree on a new baseline spending figure. Many argue that the 2% defence investment pledge agreed at the Wales Summit in 2014 is insufficient to meet the needs of European deterrence. In addition, Trump sees a new spending agreement as a key component of his transatlantic policy.

Hence, the main headline of the Hague Summit will be the adoption of a new spending goal. The target will likely be above 3% of GDP for defence items, with an additional 1.5% for broader security-related matters such as infrastructure and resilience. The sum of these two items will likely approximate the 5% figure that Trump floated at the beginning of his second term(1).

More importantly, NATO needs to decide what to spend the additional funding on – that is, what forces and capabilities to raise. That is the purpose of the NATO Defence Planning Process (NDPP). This four-year cycle is the central framework to develop the military means that are needed to defend Europe. In line with political guidance issued in 2023, NATO’s Strategic Commands identify the ‘minimum capability requirements’, that is, the pool of forces and capabilities that are necessary to fulfil operations and missions. The capability targets are then apportioned to allies(2).

The allocation of capability targets is the second ‘deliverable’ of the summit – albeit one that remains largely out of the public eye due to its classified nature. Allies are expected to agree on a 30% increase in overall targets – necessary to fulfil the requirements of the new regional plans for Euro-Atlantic defence(3). However, this increase is not going to be equally distributed across the alliance. Since the US has signalled its intention to reduce its commitments to European conventional deterrence, the European allies and Canada will carry the bulk of this increase.

Standing on weak legs?

The functioning of the alliance relies on two key assumptions that may no longer be valid. Not addressing them will make it harder to maintain a strong and credible deterrence posture.

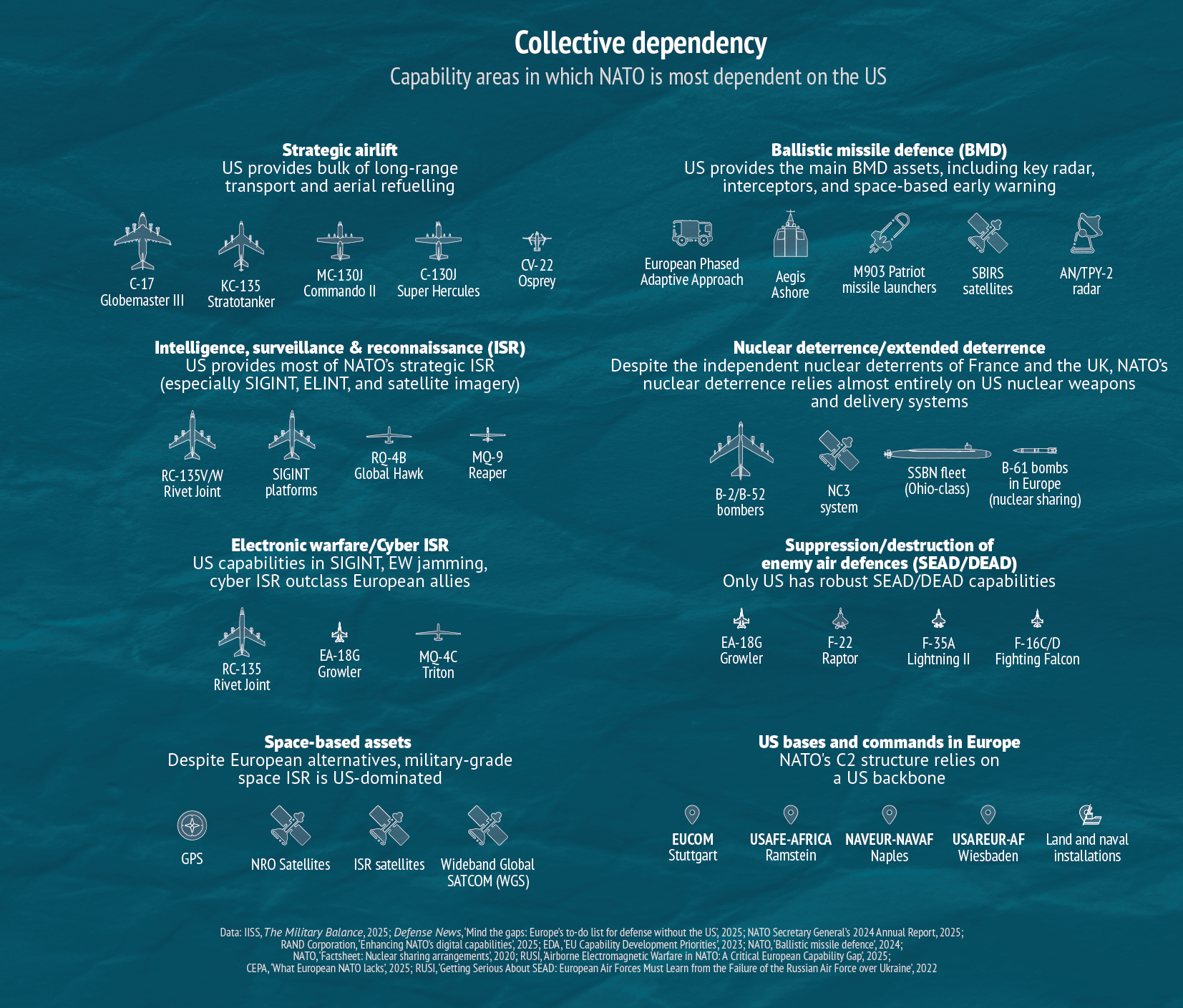

The first assumption is that the United States will maintain a key role in the deterrence and defence of Europe. NATO’s defence model relies on the US to provide large numbers of troops and firepower, including 84 000 US service members who are stationed across the United States European Command (EUCOM) area of responsibility. NATO’s Command and Control (C2) structure, too, relies on a US backbone – for instance, its highest military authority (SACEUR) is also the EUCOM commander. Finally, the US provides some key strategic enablers: intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR); air-to-air refuelling and strategic airlift; ballistic missile defence; and airborne electromagnetic warfare.

Strategic enablers are akin to collective goods for NATO: while they are provided by one country, their presence significantly enhances the combat effectiveness of all allied forces – or of specific regional coalitions. European countries have relied on American enablers for decades, even in non-NATO operations. As the continued availability of these assets was largely taken for granted, they had little incentive to invest in alternatives.

However, the new Trump administration has signalled its intention to significantly reduce its contributions, calling this long-standing assumption into question. As Secretary Hegseth said in February 2025, ‘strategic realities prevent the US from taking primary responsibility for European conventional deterrence’(4). The European Command (EUCOM) is expected to suffer cuts as part of the Department of Defense’s budget reallocation process, which may result in the reduction of American forces in Europe(5). Even the US-provided enablers could be removed from the Euro-Atlantic theatre: according to the 2025 National Defence Policy Guidance, the Pentagon will shift resources to the Indo-Pacific and ‘assume risk in other theaters’(6).

Also, the way the US coerced Ukraine in early 2025 sets a dangerous precedent: it suggests that Washington could decide to withdraw or withhold certain capabilities from European allies for negotiating purposes. In this context, it is unclear whether the US can be counted upon to maintain its commitments to Europe’s conventional deterrence – or even that any transition can be managed gradually. While the current NDPP could deal with a gradual reduction in the US presence, it is unequipped to deal with an unexpected withdrawal.

The second assumption is that individual countries can make up for capability shortfalls. While targets in the NDPP can be apportioned ‘individually, multinationally or collectively’, in practice the vast majority are allocated to individual countries. This national focus is reflected in the ‘consensus minus one’ rule: a country cannot veto a capability package assigned to itself.

According to this format, the reduction in US commitments could be offset by setting higher targets for the other 31 allies. This solution makes sense for certain forces and capabilities. For example, European countries will need to individually provide the personnel to fulfil the new NATO Force Model, which now requires up to 500 000 forces at different levels of readiness. Single countries can also provide specific assets: for instance, the UK and Canada possess significant intelligence capabilities as members of the Five Eyes alliance.

However, even the most militarily advanced European countries will struggle to replace most US-provided assets. This is particularly true for the strategic enablers, which require long-term, costly investments for acquisition and procurement. Many go beyond the means of individual countries. For example, most experts believe that Europe will need five to ten years to have sufficient capacity to stop relying on the US for space-based ISR(7).

Breaking out of the self-fulfilling prophecy

European allies in NATO may fear that they could set in motion the very outcome they seek to avoid: the more they plan to replace the US presence, the more excuses they will give to DC policymakers to leave. This fear is likely holding back attempts at openly reforming the alliance. After all, maintaining a strong bond between Europe and North America is of existential importance to NATO.

However, it is unlikely that the US will make its disengagement decisions based on which allies are providing specific capabilities. If anything, defence planners in the Pentagon may view such contributions as a positive step towards fairer burden-sharing. Even those who advocate a more restrained US role in Europe and favour a re-focus towards the Indo-Pacific argue that deterring China would be easier if Europeans possessed alternatives to US capabilities, making them more valuable allies(8). It is more likely that other policies, such as restrictions on US companies’ access to the European defence market, will rattle Trump. But it is unlikely that reforming NATO structures would make him more eager to leave.

Overcoming this fear is a necessary step to reform the alliance and make it truly fit for purpose. The alternative is maintaining the current dependency on American assets, without any guarantees that Washington will continue to provide them.

NATO’s planners would need to make some significant changes to the way the alliance decides and allocates targets. First, they need to analyse which assets the US is most likely to withdraw from the Euro-Atlantic theatre. US planners should also be more forthcoming and explain their likely plans for redeployment. On that basis, NATO should define a priority list of assets and assess how easily individual allies can replace them.

Second, in allocating capabilities, NATO planners should shift the balance away from national target allocations, encouraging European countries to develop, acquire or procure common assets. NATO commands could directly own some assets, like the AWACS aircraft or the Alliance Ground Surveillance (AGS) fleet of five RQ-4D ‘Phoenix’ remotely piloted aircraft, but this might not work for all platforms. Allies could also form groupings where higher trust facilitates the development of common assets – perhaps following the model of the capability coalitions for Ukraine, regional groups, or other flexible formats. This plan should allow Europeans to provide at least half of the enablers to accomplish NATO’s mission, rebalancing the dependency on America.

Broader changes in NATO’s force structure should also take place. The priority is to strengthen the European component of the force. One possible solution could be to group NATO’s deployed forces in Europe into larger-size units (e.g. from brigade to division). While many countries cannot immediately field larger forces, merging them with those of other countries will make each command stronger and larger(9). NATO civilian and military leadership roles can also be restructured to reflect the greater share of burden that Europeans are expected to bear, gradually moving responsibilities away from the US backbone, without completely delinking it. This could ultimately result in the appointment of a European figure as SACEUR.

While the EU cannot be directly involved in NATO structures, it has tools at its disposal that can help with the efforts outlined above. The European Commission’s proposal to activate the national escape clause of the Stability and Growth Pact will enable EU Member States in NATO to achieve higher defence spending requirements. SAFE loans will finance joint procurement projects: they are well suited to acquire key capabilities and enablers, such as those mentioned in the White Paper on the Future of European Defence. The EU and NATO agencies can also cooperate to develop joint assets, building on past successful examples such as the Multinational Multi Role Tanker Transport (MRTT) aircraft fleet for air-to-air refuelling.

A full reckoning

The two architects of the current NDPP cycle, Ambassador Angus Lapsley and Admiral Pierre Vandel, argue that it will make the alliance battle-ready ‘in a way that has not been the case since the end of the Cold War’(10). To be truly transformational, the alliance should take into account all the aspects of the new strategic scenario – including the risk of US disengagement. Only that will ensure that the necessary ambitious changes take place, such as the development of a genuine European pillar within NATO. Failure to act risks opening gaps in deterrence, making future aggression more likely.

References

- 1 Grey, A. and Bayer, L., ‘Exclusive: NATO’s Rutte floats including broader security spending to hit Trump’s 5% defence target’, Reuters, 2 May 2025.

- 2 NATO, ‘NATO Defence Planning Process’.

- 3 Ruitenberg, R., ‘NATO to ask allies for 30% capability boost, top commander says’, DefenseNews, 14 March 2025.

- 4 Sabbagh, D., ‘US no longer ”primarily focused” on Europe’s security, says Pete Hegseth’, The Guardian, 12 February 2025.

- 5 Lamothe, D., Horton, A. and Natanson, H., ‘Trump administration orders Pentagon to plan for sweeping budget cuts’, The Washington Post, 19 February 2025.

- 6 Horton, A. and Natanson, H., ‘Secret Pentagon memo on China, homeland has Heritage fingerprints’, The Washington Post, 29 March 2025.

- 7 Ruitenberg, R., ‘Mind the gaps: Europe’s to-do list for defense without the US’, DefenseNews, 25 February 2025.

- 8 Embree, J. and Beaver, W., ‘What a success story looks like: top U.S. priorities for the June 2025 NATO summit in the Hague’, The Heritage Foundation, 16 May 2025.

- 9 The Alphen Group, ‘TAG Transatlantic Compact’, 2 April 2024.

- 10 Lapsley, A., and Vandier, P., ‘Why NATO’s Defence Planning Process will transform the Alliance for decades to come’, Issue Brief, Atlantic Council, 31 March 2025.