Since the outbreak of the war in Sudan in April 2023, Turkish-made drones have emerged as a decisive element in the Sudanese Armed Forces’ military campaign, amid a conflict that has produced one of the world’s gravest humanitarian crises, with more than 12 million people displaced and thousands killed or injured. This investigation reveals how these advanced drone systems reached Sudan through opaque procurement channels and were operated with sustained external technical support—including training, maintenance, and satellite communications—raising serious legal and ethical questions about the responsibility of supplier states and manufacturers, particularly given the documented use of these weapons in densely populated civilian areas and the resulting violations of international humanitarian law.

European Centre for Strategic Studies and Policy (ECSAP)

Since the outbreak of the war in Sudan in April 2023—which has resulted in one of the world’s largest humanitarian catastrophes, with thousands killed or injured and more than 12 million people displaced—drones have emerged as a decisive weapon that has reshaped the balance of power on the ground.

This military shift, however, has come at a devastating human cost. It has intensified the risks of remote targeting in densely populated civilian environments, where airstrikes are increasingly carried out without a clear distinction between military and civilian targets.

In recent months, field sources and visual evidence have documented the Sudanese army’s use of drones to bombard residential areas and civilian infrastructure, resulting in civilian casualties. At the same time, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have announced the downing of several of these drones, including advanced Turkish-made Akıncı drones—an indication of an integrated operational infrastructure and sustained technical support enabling the use of this category of weaponry.

These developments come at a time when Sudan is subject to international restrictions on the flow of arms, amid a bloody conflict marked by grave violations of international humanitarian law.

A Decisive Weapon in a War Without Frontlines

Drones have become a central tool in the Sudanese army’s military operations, particularly as its ability to maintain ground control has declined in several areas. Military sources indicate that reliance on drones has enabled the army to carry out relatively precise strikes; at the same time, however, it has expanded the scope of collateral damage, especially in densely populated areas.

Dr. Peter Landbary, an expert in international law and the arms trade, explains that “the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) obliges States Parties to refrain from exporting weapons when there is a substantial risk that they could be used to commit war crimes or serious violations of human rights.”

He adds that although Turkey has signed the treaty, it has not ratified it, meaning that it is not legally bound by its provisions as a State Party. Nevertheless, according to Landbary, this does not absolve Ankara of its broader responsibilities under international humanitarian law and international human rights law—particularly given the Sudan conflict’s record of documented massacres, forced displacement, and crimes that may amount to crimes against humanity.

In recent months, the Sudanese army has intensified its drone strikes targeting infrastructure, accompanied by civilian fatalities. The expert concludes that the continued export of weapons to a party in a conflict of this nature places Turkey in a legal and political “grey zone,” even in the absence of a comprehensive UN arms embargo on Sudan.

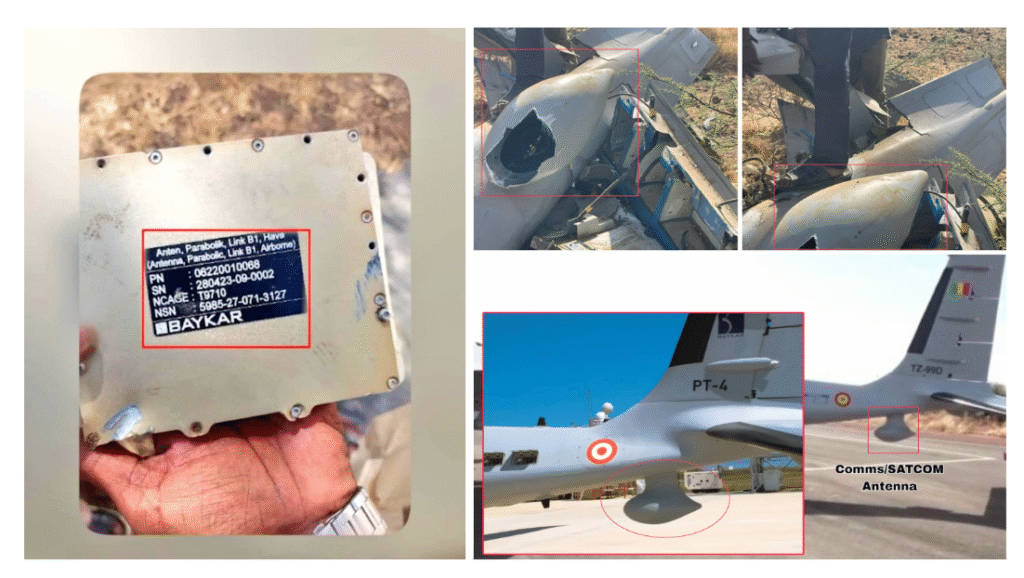

An image showing the wreckage of a Turkish-made Bayraktar Akıncı combat drone, shot down by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). The drone was being operated by the Sudanese Armed Forces and was downed over the city of Deleng in South Kordofan State, Sudan.

In South Kordofan State, over the city of Deleng, images reveal the wreckage of a combat drone that can be clearly identified as a Turkish-made Akıncı model—one of the most advanced drones in Turkey’s arsenal, typically used for long-range offensive missions.

Military aviation experts have confirmed that the characteristics visible in the wreckage—particularly the satellite communications antenna and the rear wing design—fully match those of the Akıncı platform, reinforcing the assessment that it was operated by the Sudanese Armed Forces.

How Did Turkish Drones Reach Sudan?

Findings from this investigation indicate that deals to supply Turkish drones did not proceed through transparent, direct channels. Instead, they were carried out via commercial intermediaries and shell companies registered outside Turkey.

Some of these companies ostensibly operate in sectors such as “logistics services” or “defense technologies,” without explicitly disclosing the end user or the military nature of the equipment. Informed sources explain that the process typically begins with export contracts for components or dual-use systems, registered as technical equipment or logistical support. These components are then reassembled into complete combat systems and transported through intermediary countries in the region before reaching Sudan.

This pattern is not new. It has previously been documented in conflicts such as Syria, Libya, and Yemen, where UN reports and human rights organizations have considered the use of intermediaries, shell companies, and opaque contracts as indicators of attempts to circumvent the legal and ethical constraints governing the arms trade—even in the absence of an explicit international embargo.

Such opacity makes tracing the weapons’ supply chains nearly impossible and undermines any subsequent accountability mechanisms, whether for supplier states or manufacturing companies.

UN reports and human rights organizations have also previously documented the use of Turkish drones in other conflicts, most notably in Syria, Libya, and Nagorno-Karabakh. In these cases, Turkey’s role was not limited to supply alone; it also included training, maintenance, and, at times, undisclosed operational oversight, according to reports issued by UN panels of experts.

The Turkish company Baykar is responsible for manufacturing and supplying combat drones, including the Bayraktar TB2 and Akıncı models, as well as warheads and ground control stations. Contractual data reviewed by this investigation indicate that one major contract included at least eight TB2 drones, three ground control stations, and approximately 600 warheads, with an estimated value of around $120 million.

Photos showing the wreckage of a Turkish-made Akıncı UCAV shot down by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) 8 Jan 2026.The drone was operated by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and was downed in Nyala, South Darfur, Sudan.

According to multiple sources, the company also provided technical and operational support inside Sudan to ensure the execution of the deal and the continuity of operations.

Public debate often focuses on the export of the drones themselves, while overlooking the munitions that turn them into lethal weapons. The findings of this investigation indicate that drone deals also included guided warheads designed to strike ground targets with high precision.

Experts emphasize that exporting munitions is more dangerous than exporting the platforms themselves, because munitions have no plausible civilian use, placing them squarely within the category of purely offensive weapons.

Edward Bikali, a military expert in unmanned aerial systems who previously served in the air force of a European country, explains that operating Akıncı drones cannot be done without direct technical support from the manufacturer or its authorized contractors. He adds:

“These aircraft require extensive training, regular software updates, and satellite connectivity. It is unrealistic to assume that a party fighting an internal war could operate them effectively without sustained external support.”

One of the most sensitive issues in the drone trade is the so-called End-User Certificate, the document intended to identify the final user of the weapon and its intended purpose. In the case of Sudan, no official documents have been made public clarifying the end user of the Turkish drones that have appeared on the battlefield, opening wide the possibility that the weapons were transferred or operated outside the framework declared in the contracts.

Arms-trade experts note that the absence or ambiguity of such certification is a classic indicator of attempts to circumvent legal restrictions—particularly in conflicts marked by widespread violations against civilians.

Expanding air bases… drones in service

These deals come at a time when the United States and the European Union have imposed sanctions on entities linked to the Sudanese Armed Forces, raising serious questions about the extent to which supplier actors are complying with the international rules governing the arms trade.

Recent satellite imagery shows that the Sudanese Armed Forces are expanding Wadi Sayidna Air Base, northwest of Khartoum, through the construction of three new hardened aircraft shelters. According to military experts, the design of these shelters is consistent with the requirements for protecting and operating Turkish drones used in military operations.

Analysts argue that this expansion signals a long-term reliance on drones as a core component of the army’s air strategy, rather than a temporary or ad hoc deployment.

Professor of international humanitarian law Dr. Marianne Schultz emphasizes that a state’s failure to ratify the Arms Trade Treaty “does not absolve it of the general obligation not to aid or abet the commission of war crimes,” a principle firmly established in customary international law. She notes that “providing means of warfare that are demonstrably used against civilians may open the door to indirect responsibility.”

In international law, the concept of “arms export” is not limited to the delivery of equipment alone; it also encompasses training, maintenance, software updates, and technical support. Military experts stress that the sustained operation of Turkish drones in Sudan over extended periods indicates the existence of some form of ongoing technical assistance—whether through contractors, remote updates, or on-the-ground technical teams.

Under this interpretation, the distinction between “sale” and “use” becomes legally meaningless when the operation of the weapon system itself depends on external support.

Accountability That Cannot Be Deferred

Akıncı drones rely on satellite communication systems (SATCOM) to carry out long-range missions. Technical experts note that these systems cannot operate independently of external service and connectivity providers, raising serious questions about who ensures the continuity of communication and control in a complex conflict environment such as Sudan. This technical dimension reveals an invisible layer of support that enables the use of these drones—going beyond the mere delivery of weapons to their actual operational deployment.

The converging evidence presented in this investigation—from documented wreckage, to opaque supply chains, sustained technical support, and the expansion of air infrastructure—demonstrates that Turkish drones have played a pivotal role in the ongoing war in Sudan. Even in the absence of a comprehensive UN arms embargo on the country, the nature of the conflict and the scale of documented violations against civilians impose heavy legal and ethical questions regarding the responsibility of supplier states and manufacturing companies.

In a war without clear frontlines, drones are no longer a “precision weapon” so much as a tool that expands the radius of remote targeting, increases the vulnerability of civilian life, and deepens the logic of impunity in a conflict whose end remains out of sight.

In recent years, the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights have affirmed that companies bear not only legal responsibility, but also direct ethical responsibility for how their products are used in conflict zones. Based on the facts and evidence documented in this investigation, there is an urgent need to open an independent international inquiry into the use of drones in the Sudanese conflict—one that examines supply routes, operational use, and technical support. Such an inquiry should also enable UN experts on Sudan to access air bases and sites suspected of drone operations, and ensure that these drones and their associated munitions are included in any future mechanism monitoring arms flows into the country.

In Sudan’s war, as in other conflicts, civilians were not killed by accident, but as a result of deliberate decisions made in corporate offices, government licensing authorities, and military operations rooms—decisions that allowed advanced weapons to be exported to a conflict known for its bloody record; decisions that overlooked the absence of transparency; and decisions that sustained support despite escalating violations.

Leaving this chain without accountability does not amount to neutrality—it constitutes indirect participation in the perpetuation of war. Holding accountable all those who contributed to enabling this weapon—through sale, transfer, operation, or silence—is therefore not merely a moral choice, but a fundamental condition for preventing the recurrence of crimes and for ending the logic of impunity that turns victims into numbers and wars into open markets.