London – Khartoum – Cairo – New York

As thousands of Darfur survivors continue to wait for justice nearly two decades on, the Sudanese government has been quietly advancing a parallel track silent, calculated, and woven with precise diplomatic threads aimed at rehabilitating senior figures accused of genocide and war crimes and shielding them from the reach of the International Criminal Court (ICC).

Across a sprawling network stretching from Khartoum to New York, Geneva, Cairo, and Brussels, the Sudanese state has redeployed diplomats and ambassadors from the old regime into strategically chosen foreign posts. Their role no longer resembles traditional diplomacy; rather, it operates as a “political shield” for individuals wanted by international justice.

This investigation traces, step by step, how Sudan’s diplomatic missions have evolved since 2019 into a central mechanism for protecting genocide suspects mapping how networks of influence inside the United Nations and the European Union have been mobilized to reshape the official narrative of past atrocities, deflect international pressure, and pave the way for unprecedented impunity.

Amid one of Sudan’s most complex political and human rights crises, a cohort of ambassadors and senior diplomats most of them veterans of the former regime has emerged as the front line of defense for officials wanted by the ICC, not only within Sudan but also on the platforms of the UN, the EU, and key regional capitals.

Their actions are far from coincidental. According to UN officials who spoke to the investigative team, these diplomats function as a “soft façade” enabling the political recycling of old-regime figures, acting as a protective barrier that obscures accountability and weakens global pressure for the surrender of ICC fugitives.

Omar Mohamed Ahmed Siddiq: The Architect of Sudan’s “Illegitimacy of the ICC” Narrative

At the center of the diplomatic network mobilized by Khartoum to shield officials wanted by the International Criminal Court stands Ambassador Omar Mohamed Ahmed Siddiq, one of the most influential figures shaping Sudan’s post-Bashir messaging to the international community.

During his tenure as Sudan’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations between 2019 and 2021, Siddiq played a pivotal role in reframing the state’s official narrative on the Darfur atrocities. His efforts focused on undermining the legitimacy of ICC arrest warrants issued against former president Omar al-Bashir and other senior regime figures.

According to former diplomats interviewed for this investigation, Siddiq led a coordinated campaign inside UN headquarters to recast the Darfur file as a “domestic political dispute,” one that—he insisted—did not warrant international judicial intervention.

Bill Warsen, a former UN official who spoke to the investigative team, described him succinctly: “Siddiq was the soft gateway protecting the wanted men… a loyal figure of the old regime who never actually left the stage—he simply changed seats.”

Siddiq’s influence did not fade after New York. When he later assumed the position of Director of the European and American Affairs Department at Sudan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he continued acting as the regime’s undeclared envoy. Drawing on a web of diplomatic relationships in Brussels and Geneva, he worked to ease European pressure on Khartoum and to cement the government’s preferred narrative of “judicial sovereignty” as justification for refusing to hand over ICC fugitives.

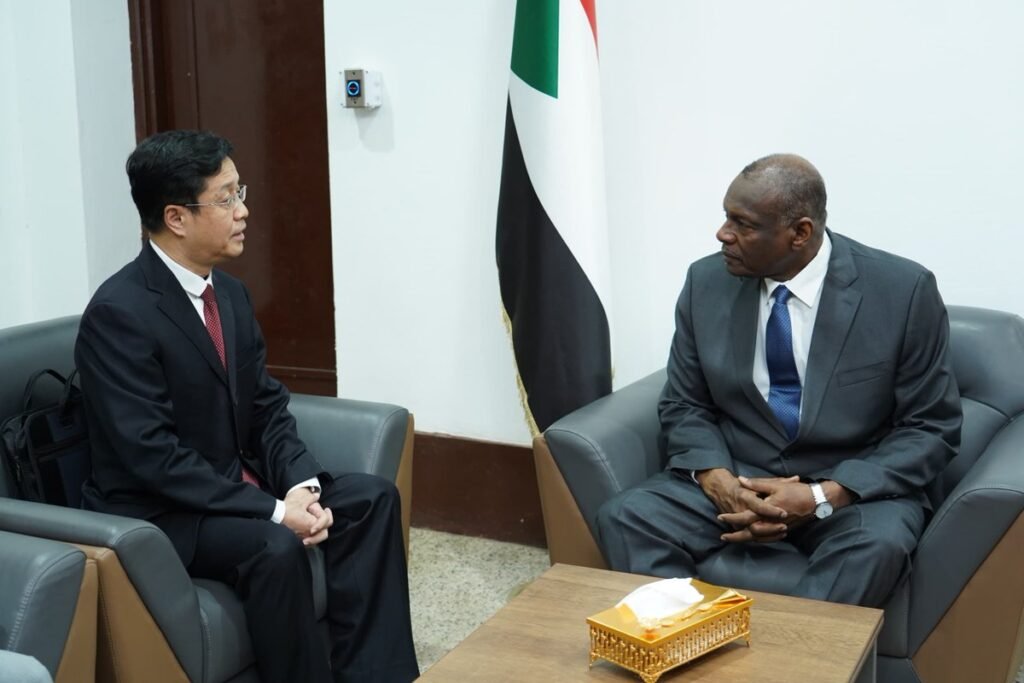

A photo shows Mohamed Ahmed Siddiq, newly appointed as Sudan’s Foreign Minister, standing alongside Zhang Xiang Hua, China’s chargé d’affaires ad interim.

A Western diplomat familiar with the file described him as: “The strategist who engineered the political shield around the Darfur suspects, a man who built a diplomatic cocoon to protect them from international justice.”

Recently appointed as Sudan’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Siddiq is no longer just a diplomat or a technocrat. He has become one of the principal architects of a political and diplomatic defense system that continues to insulate some of the most notorious figures implicated in genocide and crimes against humanity.

Dafallah Al-Haj Ali Osman – The Returnee from the Past

If Omar Siddiq is the “soft gateway” of the protection networks inside the United Nations, then Dafallah Al-Haj Ali Osman is their most forceful and unmistakable face.

A name that never truly disappeared from the scene, Osman returned to prominence whenever the authorities in Khartoum needed a diplomat capable of maneuvering within international circles to avoid handing over figures implicated in serious violations by the former regime and the Sudanese army.

Between 2010 and 2014, Osman served as Sudan’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations — years during which the regime was re-engineering its foreign relations to contain mounting pressure over the Darfur atrocities. After the fall of Omar al-Bashir in 2019, it seemed that the era of such officials had ended, but the 2021 coup brought Osman back to the center of power.

He first returned as Undersecretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Then, in a move that surprised international observers, he was appointed Acting Prime Minister in April 2025 — one of the highest executive positions in the country — despite his well-documented ties to the old regime.

A European diplomatic expert in Brussels, who has worked on the Sudan file since 2013, told the investigation team “Osman’s appointment as Acting Prime Minister is not merely administrative — it is a political message. The regime is telling the international community clearly: the figures linked to the old order still hold the levers of the state.”

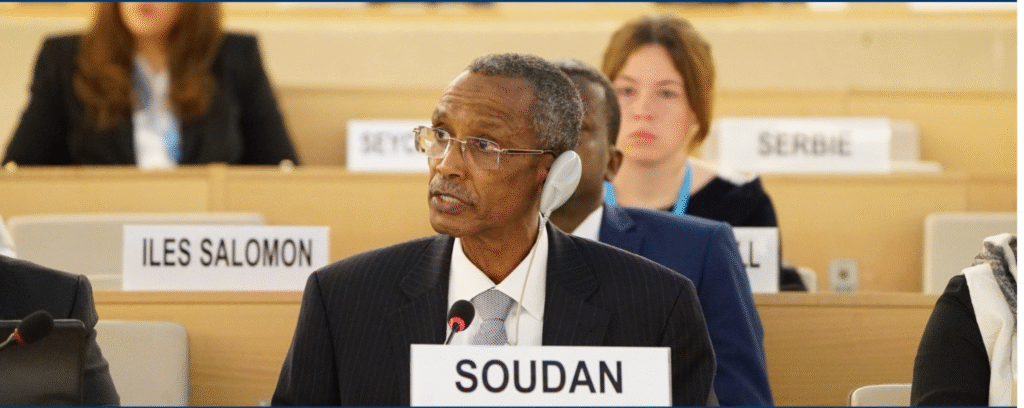

A photo shows Dafallah Al-Haj Ali Osman, who was appointed Acting Prime Minister in April 2025.

Osman moves regularly between Brussels and Riyadh in an official capacity, taking part in meetings with European Union officials on “regional stability,” all while facing no accountability for his role during the years of widespread abuses documented by international organizations under the Bashir regime.

He also played a role in restricting the access of several international investigative teams during his earlier tenure at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, relying on diplomatic arguments around “judicial sovereignty” and the “non-jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court.”

In this way, Dafallah Al-Haj Ali Osman emerges not merely as a diplomat returning from the past, but as one of the central pillars of the impunity strategy now being orchestrated from Khartoum.

Hassan Hamid Hassan… the Architect of “Process Obstruction” Inside the United Nations

Within the diplomatic network that Khartoum reactivated after the fall of the former regime, the name of Ambassador Hassan Hamid Hassan stands out. Serving as Sudan’s Deputy Permanent Representative to the United Nations in New York prior to 2020, he became known in UN corridors for his quiet yet highly effective role in diluting the findings of Sudan-related sanctions panels often preventing these reports from advancing to escalation stages at the Security Council.

According to UN officials who spoke to the investigation team, Hassan consistently worked to build voting blocs within the General Assembly usually composed of Arab and African states designed to weaken any mechanisms exerting pressure related to the International Criminal Court, whether through coordinated voting or joint statements issued under the banner of the “African Group.”

His method rested on a strategy of “emptying decisions of their substance.” As a former African diplomat at the UN put it:“Hassan Hamid acted more like a political negotiator than a diplomat. His goal was to ensure that any decision related to the ICC lost momentum long before reaching the Security Council.”

A photo shows Hassan Hamid Hassan, the Permanent Representative of the Republic of Sudan to the United Nations in Geneva

According to two sources within Arab diplomatic missions, Hamid’s influence did not stem from his official title, but from an expansive network of relationships he cultivated with Arab and African delegations. This network enabled him to lead counter-campaigns against any initiative that targeted figures from the former regime, deploying narratives of “national sovereignty” and “rejecting politicization” to stall any motion calling for cooperation with the ICC.

Hamid’s role was rarely public, yet it was decisive inside closed-door negotiations. The “real complexity” of Sudan’s justice file, according to one diplomat, began long before reports reached the Security Council at the very moment diplomats like Hassan Hamid stripped resolutions of their substance, converting what should have been binding legal texts into symbolic statements with no practical effect.

Through this approach, Hassan Hamid emerged as one of the principal architects of a “soft obstruction strategy” within the United Nations an approach in which bureaucratic maneuvering and political calculation merged to shield ICC-wanted officials from accountability.

A Diplomatic Promotion That Reveals Continuing Influence… From Geneva to Berlin and Warsaw

In Geneva—where global human-rights narratives are shaped and accountability debates unfold—Ambassador Ilham Ibrahim Mohammed Ahmed emerged as one of the most influential figures reshaping Sudan’s presence at the UN Human Rights Council in the years following the fall of the Bashir regime. Ibrahim managed Sudan’s human-rights portfolio with notable political finesse, working to redirect international discussions away from the International Criminal Court’s demands and toward narratives emphasizing “national reforms.”

But Ambassador Ibrahim’s role did not end in Geneva. In July 2025, she presented a copy of her credentials to the Polish Deputy Foreign Minister in Warsaw, ahead of her formal accreditation as Sudan’s Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to Poland—while remaining based in Berlin.

This appointment reflects a broader diplomatic strategy adopted by Khartoum since 2022, repositioning experienced figures capable of managing sensitive files within key European capitals. According to a former official in a European mission, choosing Poland—a country with significant weight inside the European Union and traditionally supportive of international justice—was “not a routine diplomatic step but a political signal that Khartoum wants a seasoned operator in one of the most sensitive capitals when it comes to ICC-related issues.”

A photo of Ambassador Ilham Ibrahim Mohamed Ahmed inside an official hall at the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Warsaw, alongside Marek Broda, the Polish Deputy Foreign Minister, during the handover of a copy of her credentials.

This appointment strengthened Ambassador Ibrahim’s access to key European decision-making circles, allowing her to expand her diplomatic efforts promoting a narrative of “domestic reform” as an alternative to international accountability mechanisms — the same role she previously played within the Human Rights Council in Geneva.

In doing so, Ilham Ibrahim has become a central node in a network stretching from Khartoum to Geneva and New York, tasked with reshaping the international narrative on Darfur by shifting the focus from atrocity crimes to administrative reform — a tactic reminiscent of strategies once deployed by countries such as Sri Lanka and Serbia before eventually acknowledging their own wartime abuses.

Imad al-Din Mostafa Adawi – the diplomat with regional backing

On the northern flank of the diplomatic influence network surrounding the Sudanese government stands Imad al-Din Mostafa Adawi, Sudan’s ambassador to Cairo and its permanent representative to the Arab League. Within diplomatic circles, Adawi is not viewed as a conventional ambassador, but rather as one of the key figures Khartoum relies on to build a “regional shield” capable of easing international pressure over the International Criminal Court’s list of wanted officials.

Adawi, who has Egyptian roots, possesses a rare ability to navigate Cairo’s political and security establishments. According to senior diplomatic sources who spoke to the team, the ambassador plays an active role in shaping back-channel communication lines between Khartoum and influential regional capitals, in an attempt to pre-empt any Western or UN pressure demanding the handover of suspects or the opening of international investigations.

Sources say Adawi consistently promotes narratives rooted in the rhetoric of the former regime — emphasizing “Sudanese sovereignty” and rejecting any external investigative track. This role, while outwardly diplomatic, goes far beyond protocol: it forms part of a broader system aimed at rehabilitating old-guard power figures by securing regional backing that dilutes international demands for accountability.

A photo of the Ambassador of the State of Qatar to the Arab Republic of Egypt during a visit to Imad al-Din Mostafa Adawi — the Ambassador of the Republic of Sudan in Cairo and its Permanent Representative to the League of Arab States.”

In a rare comment, a western diplomat who previously worked in Cairo said: ‘Adawi is not just an ambassador; he is the key conduit between Khartoum and the regional interests that intersect with the ICC fugitives’ file. His presence in Cairo gives the Sudanese leadership a political depth that is hard to replace.’

This position makes him one of the most crucial elements in the protection network operating beyond Sudan’s borders, where security interests between Khartoum and Cairo overlap, and where international justice issues become part of larger political bargains.

With roles of this nature, the contours of a foreign policy become clear—one through which Khartoum uses its diplomats not merely to represent the state, but to create a regional environment that shelters the wanted officials and guards against reopening international crimes files or advancing any serious accountability process.

How Sudan’s Diplomacy Undermines Its International Obligations

International law experts argue that what the Sudanese government is doing goes far beyond shielding ICC fugitives domestically—it constitutes a direct violation of Sudan’s legal obligations under UN Security Council Resolution 1593 (2005), which referred the Darfur situation to the International Criminal Court (ICC) and legally bound Khartoum to cooperate fully with the Court.

Instead, the state has repurposed its diplomatic apparatus to undermine this obligation by promoting a parallel political narrative that frames ICC arrest warrants as “foreign interference” or a “breach of national sovereignty.”

International legal adviser Jonathan Holmes told the investigative team: “Sudan is not merely failing to cooperate; it is building an entire foreign policy designed to obstruct international justice. This is a precedent where diplomacy becomes a legal shield for the accused.”

Experts note that placing diplomats like Omar Siddiq and Dafallah Osman in influential positions within the UN and EU allows Khartoum to create a form of legal confusion in international forums—by questioning the ICC’s jurisdiction or claiming the existence of “national investigations,” despite the absence of any meaningful judicial process inside Sudan.

Dr. Pia Lupki, a specialist in international criminal law, explains: “Any Sudanese claim of domestic prosecution holds no legal weight unless the government can demonstrate genuine, transparent judicial proceedings. So far, there is absolutely no evidence of that.”

She adds: “Khartoum’s use of diplomacy in this manner amounts to a systematic practice of impunity—one that could trigger renewed Security Council action or targeted sanctions against officials obstructing international justice.”

This legal dimension shows that the issue is no longer mere political reluctance—it is a deliberate effort to dismantle the international justice framework, a move that threatens not only the future of accountability for Darfur but also raises the risk of repeating similar atrocities in Sudan’s ongoing conflicts.

A Diplomatic Network Functioning as a “Political Defense Line” for ICC Fugitives

Tracing the trajectories of the three diplomats—Omar Siddiq, Dafallah Haj Ali Osman, and Imad al-Din Adawi—reveals a clear pattern: a deliberately reassembled diplomatic network stretching from New York to Riyadh, Cairo, and Brussels, designed not merely to polish Sudan’s international image but to engineer a global environment that shields key suspects of genocide from international pressure.

Since 2022, Sudan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has pursued an unofficial strategy of “repositioning trusted cadres of the former regime” into posts that allow them to influence the global narrative surrounding the ICC.

A senior former EU official working on the Sudan file told the investigative team: “It was clear we were not dealing with ordinary diplomats. These individuals operated like a shadow institution whose first mission was to protect the old regime and its men.”

Evidence shows that this network operates through three primary mechanisms:

- Promoting political messaging that delegitimizes the ICC, repeating the old regime’s narrative that the Court is a “Western tool for political manipulation”—the same argument used by Khartoum since 2009.

- Participating in official meetings presenting Sudan as a country pursuing “reform.”

In reality, the government was simultaneously recycling ICC suspects into influential military and governmental positions, granting them broad protections and integrating them into state structures. - Using diplomacy as a personal shield for ICC fugitives by reframing them—particularly al-Bashir, Hussein, and Haroun—as integral figures in a “political transition,” while implying that any discussion of their handover could “destabilize the country.”

A European official recounted: “Whenever we raised a question about the ICC, the delegation simply smiled and said: ‘This is outside the scope of this meeting.’”

Findings gathered by the investigation indicate that, since 2021, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has re-emerged as one of the key institutions of the “deep state,” regaining its influence despite the shifting political landscape in Khartoum. Externally, the diplomatic messaging remains unchanged: shield the old guard from any form of accountability.

In this context, international lawyer Nellie Warwick, who has studied the Darfur file extensively, explains: “It’s not only about refusing to hand them over. There is a diplomatic network actively reshaping the international image of the accused—separating politics from justice while exploiting loopholes in the global system.”

Justice on Hold… and Diplomacy that Re-Creates Impunity

As the threads of this network stretch from Khartoum to New York, Cairo, Brussels, and Riyadh, one reality becomes clear: protecting International Criminal Court (ICC) fugitives is no longer just a political decision inside Sudan. It has evolved into a fully engineered diplomatic project, operated through carefully recycled diplomats whose primary mission is to keep the old regime’s most notorious figures beyond the reach of justice.

A senior official within the Sudanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs — who requested anonymity — told the investigation team that the ministry maintains internal lists of “trusted” diplomats from the former regime, strategically redeploying them to posts involving “sensitive files,” particularly in New York and Geneva.

While Sudan’s government continues to invoke narratives of “judicial sovereignty” and “national stability,” the evidence reveals a systematic effort to reproduce impunity — shaping political narratives, influencing international forums, and providing diplomatic cover and regional alliances for ICC fugitives.

Meanwhile, survivors of Darfur, families of the dead, and communities displaced for two decades remain suspended between politics, bureaucracy, and international silence. As the doors of embassies open to Bashir’s men, the doors of justice remain firmly closed to the victims.

International justice expert Dr. Roberto Della Valle notes: “Sudan’s diplomatic behavior does not simply reflect a desire to obstruct justice — it reflects an attempt to rebuild an institutional protection network, similar to post-atrocity governments elsewhere.”

If this network continues — both at home and abroad — it threatens not only the trajectory of transitional justice in Sudan, but also reshapes a broader regional landscape of unchecked impunity, sending a dangerous message: In Sudan, impunity may change its form — but it does not disappear.

And as dark as this reality appears, growing international pressure, rigorous documentation efforts, and cross-border accountability mechanisms remain the last tools capable of breaking this diplomatic shield — and of restoring the Darfur genocide to the center of the global justice agenda.

The question that has lingered since 2003 — “When will the perpetrators be held accountable?”

now evolves into a more urgent one: “Who will hold accountable the system designed to protect them from justice?”

When Diplomacy Becomes a Defense Line for Suspects

What Khartoum is doing today is not an isolated anomaly in the landscape of international justice. According to researchers in transitional justice, the Sudanese diplomatic networks — in their structure and functions — closely resemble patterns seen in other countries that faced major war-crimes investigations.

In Libya after 2011, organized efforts sought to obstruct ICC arrest warrants targeting figures from the former regime. Parallel diplomatic networks were quietly created to recycle old officials and promote narratives questioning the Court’s jurisdiction.

In Serbia during the 1990s, Belgrade relied on a tightly coordinated diplomatic and media machine to persuade European capitals that those accused of atrocities in Bosnia were “essential to national stability.” That strategy delayed the surrender of many suspects for years, until trials finally proceeded in The Hague.

In Rwanda before the establishment of the Arusha Tribunal, the Hutu-led government deployed a diplomatic discourse aimed at downplaying state responsibility for mass killings, reframing the genocide as “internal disturbances.” Foreign missions were used as channels to reduce international pressure and block any meaningful investigation until the regime collapsed.

These examples, according to Dr. Roberto Della Valle, reveal a recurring global pattern:

When political leaders face sweeping accusations of crimes against humanity, diplomatic missions often shift from representing the nation to constructing narratives of protection for those in power.

Experts argue that what is unfolding in Sudan today fits squarely within this pattern. Diplomacy is being used as a political and legal shield, designed to keep ICC suspects beyond the reach of accountability and to delay justice for as long as the international system allows.