European Center for Strategic Analysis and Policy (ECSAP)

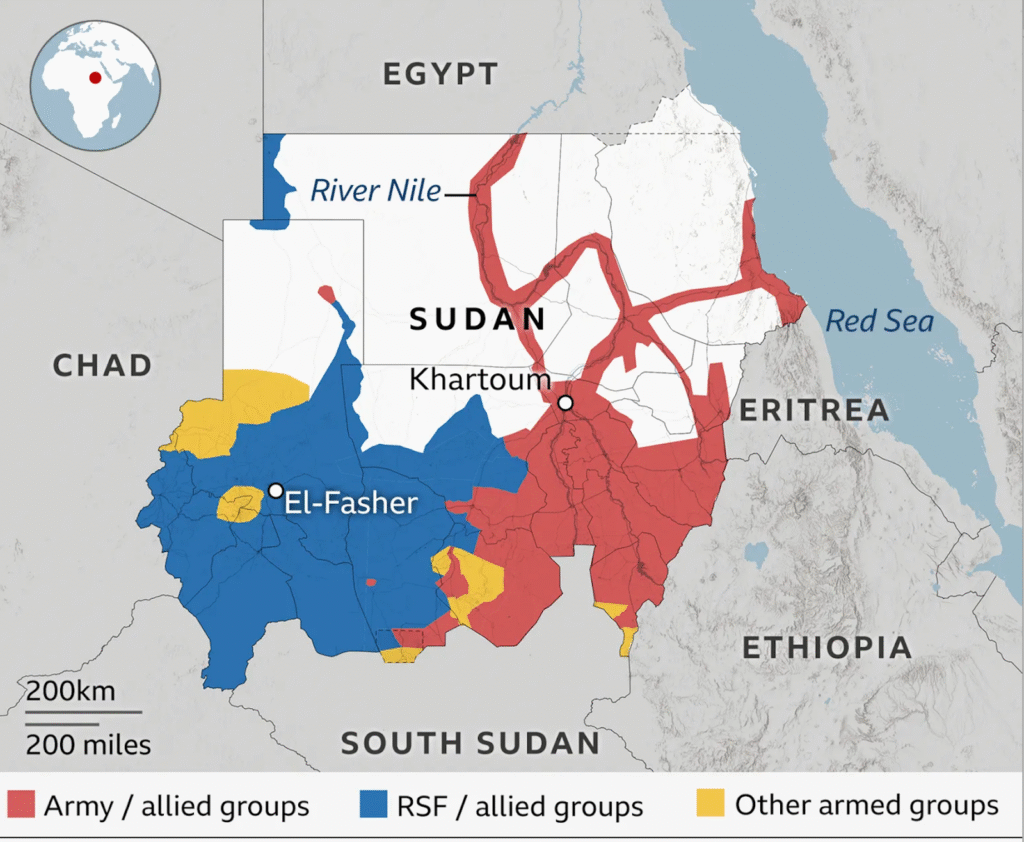

Over two years of conflict that have torn Sudan apart, the Sudanese army has remained capable of sustaining high-tempo military operations despite economic collapse, dwindling resources, and the breakdown of internal supply routes. A single question echoed among survivors, researchers, and international actors alike: Where is the weaponry coming from? Who is financing the continuation of this war?

While cities were bombed, homes burned, and displaced families fled from one area to another, undisclosed supply corridors were moving across borders:

- Cargo ships passing through ports along the Red Sea

- Military cargo aircraft landing at night in restricted airfields

- Front companies established in free zones to facilitate shipments labeled under “logistics services” and “humanitarian aid”

Preliminary documents, flight and maritime tracking data, and field testimonies from former officials and port workers indicate the existence of an aerial, maritime, and logistical supply network that has enabled the Sudanese army to maintain elevated combat capacity since April 2023.

The evidence suggests that Egypt plays a central regional role in this network—whether through air and port facilitation, or through commercial intermediaries and shell companies used to disguise the nature of the shipments under the cover of “humanitarian assistance.”

However, on the ground, aid did not reach hospitals or displacement camps.

What arrived instead were:

- Artillery shells

- Ammunition shipments

- Improvised barrel bombs

- Dual-use chemical materials suspected of being converted into choking agents

Egypt’s Supply Route: A Shadow Logistics Network

Information gathered by the investigation team indicates the existence of a coordinated air and maritime support channel in which Egypt played a central role, enabling the Sudanese army to sustain combat operations despite economic collapse and the depletion of local resources.

Flight-tracking data reveal repeated landings of an Egyptian military transport aircraft, an Ilyushin Il-76MF with registration SU-BTX—at both Wadi Sayidna Air Base and Merowe Airport, during periods that coincide with intensified aerial bombardment in northern Darfur.

This aircraft is part of Egypt’s military transport fleet and is typically used to move support equipment and logistical supplies. The cargo details were not listed in public records, a pattern commonly observed in shipments with military or sensitive payloads.

These deliveries arrived at night and were unloaded under direct military guard, without official logging of the cargo contents.

A former Sudanese army officer told the investigation team: “The shipments were offloaded with no paperwork. There was no official record of what they contained. Everything was moved directly into sealed storage facilities overseen by units tied to the air force command.”

Egypt supplied the Sudanese army with armed combat drones.

Field testimonies indicate that government forces used these drones to carry out strikes with guided aerial munitions. Egypt also supplied the Sudanese army with heavy artillery shells that were used to bombard densely populated neighborhoods, in addition to manually deployed barrel bombs dropped from aircraft — and, according to weapons experts interviewed by the team, materials that may have been converted into chemical agents.

In the city of El-Fasher, human rights organizations and local activists have documented the bombing of homes, markets, and displacement shelters by the Sudanese army using unmanned aerial vehicles.

Malik al-Din Abdullah, a Sudanese rescue worker and one of the witnesses to the bombardment of Omdurman, told the investigation team:

“Every time the Sudanese army bombed neighborhoods in El-Fasher, there were no military targets to hit. We heard the aircraft circling over the residential areas, and then something like a barrel would fall. It wasn’t a single explosion — the ground itself shook.”

Meanwhile, Khadija Mohammed, a member of a medical response team in North Darfur, said in a phone call:

“Most of the bodies we recovered were women and children. It was clear the bombing was not targeting combatants.”

According to the Yale Humanitarian Research Lab, which monitors North Darfur via satellite imagery:

“Indiscriminate attacks on residential areas — even when a military target is present — constitute a war crime if precautions to protect civilians are not taken. If the targeting is deliberate, it may amount to a crime against humanity.”

Yet while the cities were being destroyed, a continuous financial and logistical supply chain was operating in the background — ensuring the Sudanese army could sustain its military operations at a steady pace.

Drones: Technical Transfer and Targeted Training

Egypt possesses a varied arsenal of armed unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), including Wing Loong I and II systems, in addition to medium-range reconnaissance drones, and operates specialized training centers for drone operation units.

The emergence of new offensive drone capabilities within the Sudanese army coincided with nighttime cargo flights linked to Egyptian airbases, undisclosed joint training activities, and a noticeable shift in the type of munitions used in the bombardment of El-Fasher.

RSF Forces Down an Egyptian Drone Used by the Sudanese Army

Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have reportedly shot down an Egyptian-made drone being operated by the Sudanese army.

Analysis of strike patterns in El-Fasher indicates the use of Blue Arrow and AKD-series air-to-ground munitions—both compatible with Wing Loong drone launch systems—further reinforcing the assessment that technical expertise, drone components, and/or munitions were transferred to Sudan.

On the maritime level, AIS shipping data shows container and mid-sized cargo vessels tracked at Red Sea ports carrying shipments labeled as “construction equipment” or “logistics supplies.” However, post-unloading inspections revealed military materiel and spare parts inside. Several of these routes passed through Egyptian ports or via the Suez Canal, which connects shipping flows between the Gulf and the Red Sea.

In addition, witnesses from relief teams in North Darfur reported a recurring pattern in the drones’ flight behavior: the UAVs hovered at a medium altitude for several minutes before the strike, carefully selecting impact points on the trucks (specifically the cargo compartments rather than the driver’s cabins), followed by an immediate withdrawal after the strike, without conducting a secondary attack.

Such tactics are not typical of indiscriminate fire. They require a prepared ground control station, live video feed through thermal or electro-optical cameras, and trained crews capable of distinguishing a moving target from civilian vehicles.

Therefore, what is evident in the field is not merely the presence of Egyptian drones, but full military teams responsible for their operation and targeting.

Ports — “Relief” Containers with Military Cargo

Shipping data shows that containers labeled in their paperwork as “construction equipment” or “relief materials”traveled through commercial routes via the Suez Canal and Red Sea ports to Port Sudan. However, testimonies from port clearing and loading workers — some of whom spoke to the team under protection — tell a different story. When the containers were opened during unloading, standard wooden crates were found containing clearly military items: artillery shells, ammunition shipments, spare parts for military equipment, thermobaric rocket launchers, man-portable anti-tank weapons such as the M79 “Osa”, and 9M133-1 “Kornet-E” guided anti-tank missiles — while the official shipping documents continued to describe the cargo as civilian.

Photographs show Sudanese army fighters carrying M79 “Osa” anti-tank launchers and 9M133-1 “Kornet-E” guided anti-tank missiles supplied by Egypt.

A port clearance employee told us: “The shipments come from Egypt with humanitarian paperwork, but when we unload them, we find shells and spare parts. We are not allowed to approach or ask questions.”

A consistent pattern across multiple testimonies was that unloading usually took place at night, under direct military guard, after sealing off the port area from civilians and humanitarian organizations — isolating the unloading process from normal oversight. Witnesses also noted containers being force-opened and resealed, or moved directly to restricted military storage areas inaccessible to civilian workers.

Images show several RPO-A “Shmel” thermobaric rocket launchers — a rare system — delivered by the Egyptian army to the Sudanese army, along with 60mm mortar shells left behind by Sudanese forces during the withdrawal from El-Fasher.

Evidence of discrepancies between declared contents and shipment documents includes mismatches in container numbers between final bills of lading and AIS tracking displays, and the presence of standardized wooden crates commonly used worldwide to package ammunition.

Three informed sources also reported the arrival from Egypt of industrial chemical materials that can be converted into choking agents, shipped under the label “water purification,” as well as high-pressure pumps and unloading systems that can be used to process gases. Medical teams in Darfur described symptoms consistent with exposure to irritating gases.

Khadija Mohammed, a nurse from Darfur, told the team: “Some cases arrived without visible physical injuries, but with severe choking and spasms. This was not ordinary bombing.”

Richard Dano, a former expert at the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, commented: “The presence of dual-use chemicals does not necessarily mean chemical weapons have been used, but their presence combined with barrel-bombing tactics raises the level of risk to an extremely high degree.”

Middlemen companies: money before weapons

The investigation found that many of the financial transfers linked to these shipments did not come directly from declared official budgets; instead they were routed through logistics and service companies and shell firms registered outside Sudan—often in regional financial centers—intended to facilitate payment in hard currency and create apparently commercial records. Documents reviewed by our team record vague line-items such as “urgent government support,” “operational services,” or “relief allocations,” phrasing commonly used to conceal the true purpose of transfers.

The result is that money often precedes weapons: funding is paid to intermediary companies that in turn organise contracts and shipments and secure clearance for sea and air movements, making the true sources of financing harder to trace and insulating the real actors behind commercial façades. Legal and financial verification will require access to bank records (SWIFT), contracts of intermediary firms, account statements for shell companies, and payment vouchers that reveal the concealment of funding sources.

Decision-making chain inside the Sudanese army

Documents and testimonies reveal that the decision to employ air strikes and barrel bombs in Sudan is not taken randomly or at a low tactical level, but issues from a narrow, centralized chain of command.

According to three informed military sources, the decision-making path begins inside the Transitional Military Council, where Lieutenant General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan gives the final approvals for large-scale air operations. No strategic strike, especially those that target populated areas, proceeds without authorization at the highest political-military level.

Orders then move to the Air Force command, which prepares flight plans, selects the types of munitions, defines air routes, and designates “targets” that are sometimes loosely classified as “areas of enemy activity,” a classification that effectively broadens the scope of strikes to include residential neighborhoods and displacement camps.

The actual execution is carried out by specialized air units trained to perform low-altitude bombardment and to drop barrel bombs. Sources indicate these units operate with field liaison officers who carry out direct targeting guidance during strikes, including giving the “release” signal for explosive payloads.

This hierarchical structure, which links a central political decision to a coherent military and technical execution plan, shows that the bombardment was not the result of battlefield chaos or isolated mistakes, but the product of an organized policy that was protected and sustained through clear command channels.

Accordingly, the chain of responsibility begins at the political top, passes through a specialized air command, and ends with field execution units—a sequence that can be traced, documented, and held to account under international law.

Those who pay the price at every stage are the civilians whose neighborhoods have been turned into open lines of fire.

The Result on the Ground: The Destruction of Entire Cities

Satellite imagery analyzed in cooperation with a leading research center reveals a pattern of systematic destruction in the city of El-Fasher. A comparison of pre-conflict and post-conflict images shows that more than 42% of the city’s neighborhoods have been completely destroyed or severely damaged: residential buildings collapsed or burned, roads rendered unusable, and repeated burn patterns that indicate successive targeted strikes rather than a single incident.

This loss of physical space represents more than buildings—it means the erasure of homes, livelihoods, schools, and healthcare facilities, the kinds of civilian infrastructure that cannot be easily replaced.

Field documentation supports the satellite evidence: schools reduced to rubble, hospitals stripped of equipment or repeatedly struck, and three displacement camps that were bombarded multiple times, forcing a second wave of displacement for thousands of families who had already fled once.

Medical workers described to investigators scenes of “urban warfare tactics” where no meaningful distinction was made between civilian and military targets, intensifying civilian suffering and undermining all efforts at relief and shelter.

A chronological analysis of the strikes indicates that these were not isolated targeting errors or occasional exchanges of fire, but rather a repeated pattern affecting specific civilian sites — markets, hospitals, schools — to a degree that strongly suggests the presence of a deliberate policy or operational tactic.

The Conflict Is Not Only Sudanese

What is unfolding in Sudan goes beyond an internal conflict. It intersects with regional power calculations and spheres of influence. Our analysis of regional networks, financing channels, and logistical supply lines shows that several regional actors hold direct strategic interests in the Red Sea corridor and Sudan’s borderlands. As a result, Sudan is treated as a security and geopolitical file, rather than a purely domestic crisis.

Researcher Marit Andersen summarizes this dimension: “Sudan is not a civil war. It is an arena for the redrawing of regional power balances.”

She adds: “Egypt seeks to maintain its security influence and ensure stability along its southern border. This structure turns Sudan into a space where external interests intersect—interests that may, by action or by neglect, contribute to sustaining the machinery of violence.”

Andersen further explains: “Cairo does not want a strong, fully sovereign Sudan—nor a completely collapsed Sudan. It wants a Sudan whose decision-making remains shapeable. Military support becomes a tool to manage balance rather than to decide the war.”

Wars Do Not Erupt on Their Own

This investigation shows that the war in Sudan was not merely the result of internal collapse; it is the product of a complex network of financing, logistics, and political backing that crossed borders quietly. Evidence ranging from shipping and flight records to testimonies from field workers demonstrates that maintaining the current scale of military operations would not have been possible without a coordinated Egyptian supply infrastructure of weapons and materiel.

The impact of this support was not limited to shifting front-line balances; it translated directly into the lives of civilians. Every fuel shipment delivered, every batch of ammunition transported, ultimately reached homes, streets, and displacement camps. For that reason, responsibility does not rest solely with the one who pulled the trigger but with every actor who enabled and sustained the machinery of war.

Tracing the flow of weapons and money is not only a journalistic exercise; it is a step toward accountability. Just and meaningful accountability begins by identifying who decided, who remained silent, who facilitated, and who benefited.

And in the absence of reliable avenues for justice within Sudan, the supply lines themselves become the key to understanding the roots of the conflict and to preventing its repetition.